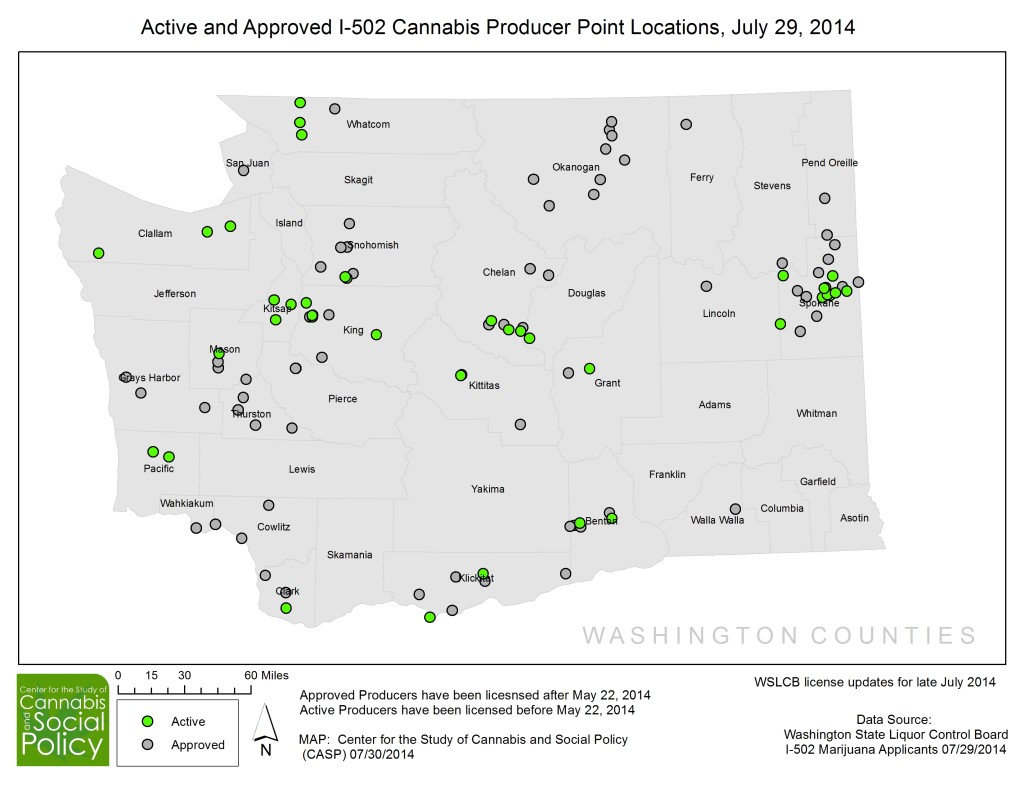

Map by Steve Hyde and Steven Wan

by Dominic Corva, Executive Director

Part V of this series turns our attention to the notion that I-502 is meant to eliminate the black market right away, and that it is sensible to judge the existing state of legal market capture by whether it is in fact making a dent in illegal cannabis markets.

These notions are wrong. The shortage is not the story, and it doesn’t matter at all in the short and medium turn how quickly legal cannabis markets develop in order for I-502 to realize its most important social goal.

Why isn’t the shortage the story?

The “shortage” is a stage in the process of market creation, not an anomaly. The real story is, what stage are we at in the process of market creation? We are at the stage where reliable information is scarce; not many retailers are open; production is coming on line; and a significant percentage of applications have yet to be approved. The latter seems to be the only explanation on offer in corporate media coverage of I-502 roll out. We have established in the other four parts of this series that there are more complex conditions at work than simple WSLCB approval. Therefore, the shortage is not the story.

If we think about the “shortage” as a completely expected situation on an historical trajectory towards market creation, we can turn our attention to other issues identified in the press as social policy concerns. Once again, let’s use the Stranger’s coverage as an example. Has Washington State in fact screwed up its “legal pot system“?

“If it fails to replace the black market, if it fails to extract profits from cartels and the gangs still get rich, if drugs are still easier and cheaper to buy on the street, and if we fail to make pot an above-board industry? Then it becomes a warning to other states, and fodder for those who argue the illegal pot market is unbeatable and legal regulation is too quixotic for America to pursue.

Which is why Washington’s experiment is off to a concerning start.

Most troubling, the system that kicks off Tuesday is designed to replace less than 10 percent of the state’s black market for pot.”

No one disputes that an important legitimizing discourse for I-502 proponents is the movement from unregulated to regulated cannabis commerce. However, no one with any knowledge of how the black market works would demand that I-502 be deemed a failure for this not happening right away. Current illegal and medical market consumers have little incentive to buy from the legal market, and won’t until prices become competitive. In order for prices to become competitive, the market creation process has to mature. A significant portion of daily cannabis consumers are embedded in social networks of cannabis production that reduce the cost of their own consumption: they buy enough to resell to their friends and consume for “free.” They won’t be able to do that with limited quantities and high prices available under I-502. That said, is there any reason to pose this draconian “legal” versus “black market” discourse, as though the two are inherently antagonistic?

The first thing we need to understand is how important the black market is for getting the legal market off the ground. As each producer enters their 15 day window, thousands and thousands of seeds and clones from the black market establish the conditions necessary for legal production to happen. There is no way to estimate which sources are the most important, but here are a few: Dutch seed companies; Canadian seed companies; U.S. “medical” seed companies for whom the first part of the transaction is gray but as soon as those genetics cross state lines become a Federal offense; U.S. medical clone operations that far exceed established medical limits to production; and non-medical versions of the last two. So first of all, the black market is foundational for the legal market to get off the ground, and thinking about the black market strictly in terms of competition is extremely problematic.

Second, every last master gardener employed by I-502 companies, and most of the I-502 business community got their start in the black market. All of them. They are utilizing their black market experience and networks to acquire genetics and get help with getting their businesses off the ground, often from black market operators who will continue to operate in the black market. This optimizes the development of the legal market, on the one hand, and provides an avenue for medical and illegal producers to become “legitimate” as they bootstrap into now-legal professions. The more these paths are cleared, the sooner many clandestine careers will become successful, professional careers. This is happening no matter where we are in the stage of market creation, and probably can’t be quantified. But it is a vital part of the long-term goal of I-502, to reduce and eventually eliminate illegal cannabis markets.

Third, legal markets are designed to operate completely separately from illegal and medical markets once the 15 day window is over. Legal production, processing, and retail are regulated tightly and therefore separate from illegal and medical markets. This applies to legal consumers too. Legal consumers are the last stage of the new market chain, not legal retailers. Like legal producers, processors, and retailers, they should be considered a distinct subset of cannabis markets and consumers. It was never a given that everyone who consumed cannabis would automatically switch to legal cannabis consumption: it is a choice structured by conditions of choosing. What are those conditions?

Legal retail prices are at least double those of medical and illegal retail prices. Therefore legal cannabis consumers have to be willing to pay more for legal cannabis, and the reasons why anyone would be willing to pay more for an inferior product with less choice (so far) need to be investigated. Likely explanations include: folks with more disposable income, brand new consumers without access to medical and illegal cannabis; tourists; and people for whom it is a moral, ethical, or political choice to consume legal cannabis. The Stranger’s Dominic Holden recently published an essay arguing for the latter.

With limited retail shops open, current “high” prices at $15-$30/gram are still low enough to clear the shelves, as evidenced by Seattle’s Cannabis City opening and closing twice already. This is exactly the condition many retailers who are coming on line hope to avoid: they are waiting till they have supply contracts lined up so that they can stay open instead of paying overhead while supply hiccups get worked out. Notice, at these prices, supply runs out: this means that prices could actually be higher — but they aren’t, for non-business reasons. Many retailers are reluctant to charge higher prices. I won’t go into those reasons here, because I haven’t talked to enough of them, but so far there seems to be a reluctance to charge consumers beyond a certain price.

Given that the black market exists in a social dialectic with other cannabis markets, not in a mutually exclusive competition, we must still ask whether and how much this is even a problem of which we should be concerned, with respect to evaluating I-502 purpose and social policy outcomes.

Does it matter how quickly legal cannabis markets develop, for that evaluation? Not if we remember that the primary goal for passing I-502 was not in fact the creation of legal cannabis markets. The primary social goal for cannabis legalization is de-incarceration. This will be the subject of Part VI. Stay tuned.