Author: corvad

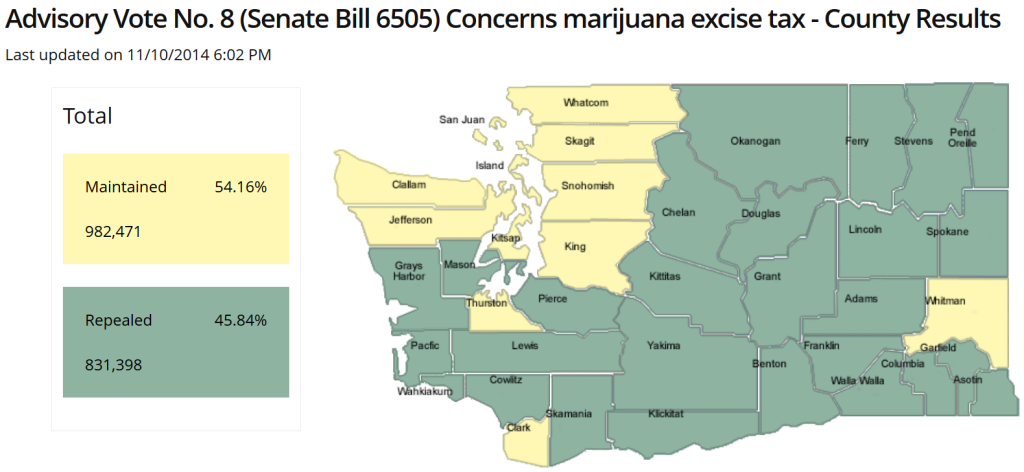

County Voting on Advisory Vote #8

Map Source: http://results.vote.wa.gov/results/current/Advisory-Votes-Advisory-Vote-No-8-Senate-Bill-6505-Concerns-marijuana-excise-tax_ByCounty.html

By Dr. Jim MacRae, CASP Research Associate

Counties that chose, on Advisory Vote #8, the option to MAINTAIN the restrictions imposed by SB-6505 on common benefits and tax exemptions available to the remainder of Washington’s agricultural businesses tend to cluster in the Northwest portion of the State and are joined by Clark and Whitman Counties.

The negative correlation apparent in the following graph demonstrates that Counties voting for the legalization of recreational cannabis in 2012 have now expressed a preference to maintain the exclusion of common agricultural benefits and tax exemptions delineated in SB-6505.

MAINTAINING SB-6505 increases the production costs (and, in many cases, processor costs) of recreational cannabis. Given this, one might have reasonably expected to see less desire to maintain SB-6505 in areas that are on record as supporting the legalization of recreational cannabis. This is clearly not the case.

Perhaps this reflects enduring support for one of the original selling points behind I-502: the supply of new tax revenues to our State. Those favoring SB-6505 as one that eliminates tax exemptions to I-502 businesses may not wish to see the promised tax revenues they voted for in 2012 be compromised.

Conversely, those wishing to repeal SB-6505 as something that dramatically increases the cost of production of recreational cannabis (in a manner further compounded by the the multiple levels of subsequent excise tax) may well have realized that maintaining SB-6505 will increase both the cost of recreational cannabis to the consumer, and the difficulty of running a profitable I-502 business.

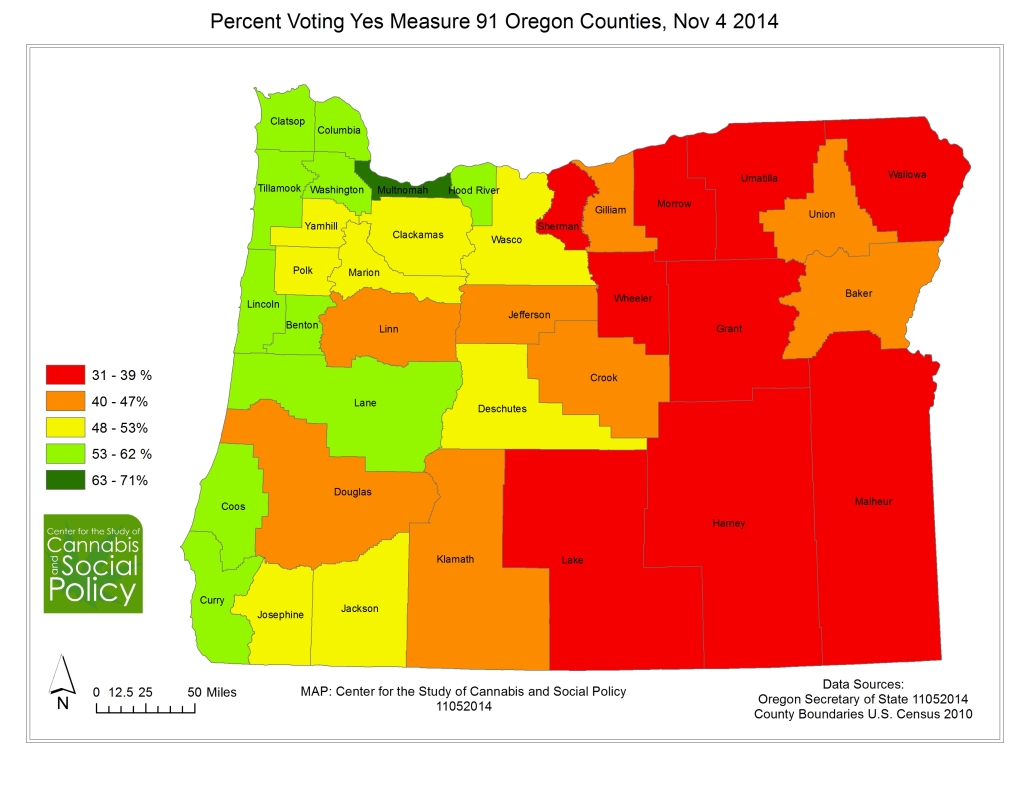

Cultural Geography of WA State Cannabis Consumption (based on BOTEC study)

Map by Steve Hyde

Research by Dr. Jim MacRae

by Dominic Corva

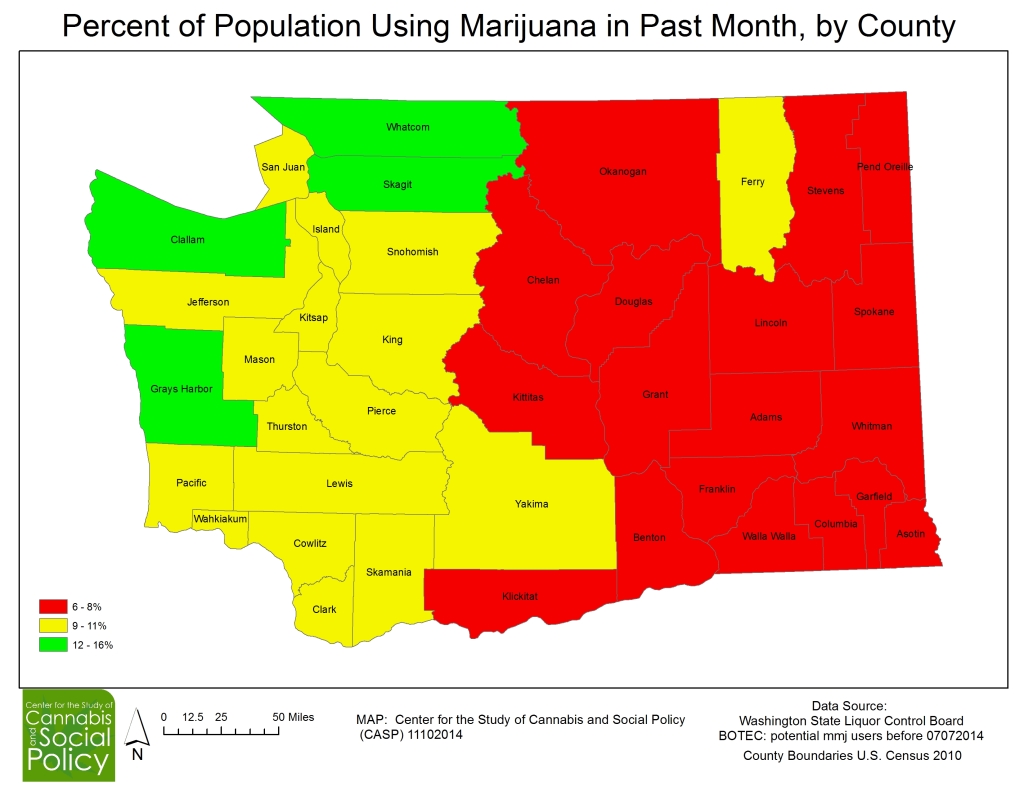

This map, created from data produced by BOTEC for the Washington State Liquor Control Board, shows how the WSLCB understood the cultural geography of cannabis consumption by county level in Washington State as they embarked upon their rule-making process. This information was used to calculate canopy limits and allocate retail stores to jurisdictions a year ago.

The purpose of creating this map is two fold: first, to help the public and policymakers understand how cultural geography shapes bureaucratic rulemaking; and second, to help the public and policy makers understand better how cannabis market consumption (not just legal consumption) is unevenly distributed throughout the state.

This “one-map story” is the first in an ongoing series aimed at helping people understand the geography of cannabis policy landscapes, one digestible bit at a time. More complex analyses depend upon understanding how all the stories fit together, but the following paragraphs provide starting points for such analyses.

First, there is a clear East/West relationship may map, to some extent, onto existing state political geographies: conservative/liberal; rural/urban; and to the I-5 corridor which extends south of the border but also north of the border. We could look further at the first two by finding existing county-level maps, but the third requires a little more thought.

While I-90 is a major East-West corridor, it does not lead through major urban consumption areas. The North-South corridor leads to and through Vancouver, Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, and Eugene; from Eugene to the south is the cannabis agricultural breadbaskets of Southern Oregon and Northern California. It’s also the major historical corridor for hippie migration from the Bay Area at the end of the 1960s.

We can also say with weak confidence (given data limitations and methodological challenges) that there appear to be five anomalous counties: Three of them (Whatcom, Skagit, and Clallam) are in the Northwest of the state, where lots of intentional communities sprang up in the 1970s. We also note that southwest British Colombia may have stronger cultural geographies of consumption that Washington state. Grey’s Harbor is on the Peninsula not far from where Ed Rosenthal outed the first commercial indoor grow he’d ever seen in a 1987 Whole Earth Catalog article; and Ferry county in the northeast may share some combination of the Northwest cannabis consumption geographies as well as being a historical corridor for BC cannabis entering the U.S. (this all-but ended after 2001).

One map stories root our geographical investigations by showing us spatial relationships that must be further explained. Look forward to more on a regular basis!

[Photo Essay] State-Legal Sun-grown Production in Washington State

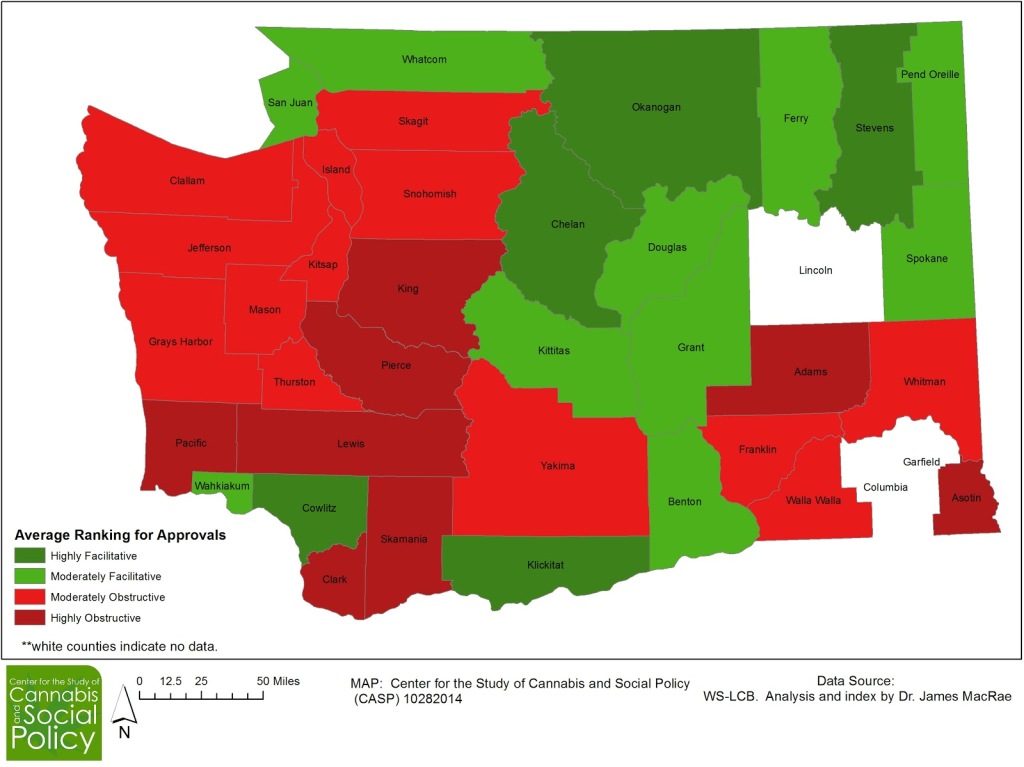

Obstructive and facilitative County environments with respect to I-502 permitting in Washington State

by Dr. Jim MacRae*, CASP Research Associate and Dr. Dominic Corva, CASP Executive Director

Maps by Steve Hyde and Steven Wan

*This work evolved from work done by Dr. MacRae as public input responding to Snohomish County’s moratorium decision. Our choice of Snohomish County to serve as the our detailed case study was influenced by this fact.

The recent wave of moratorium fever in Washington State, exemplified by recent events in Snohomish and other Counties and Cities (see here and here), poses unforeseen challenges for the rollout of legal cannabis. Local resistance does not necessarily foreclose legal cannabis business in general, but on where and what kind of legal cannabis businesses are allowed to operate within the State. Instead of a State-level “laboratory of democracy,” what is developing is a patchwork of more- and less-friendly policy environments shaped by localized political and economic interests. This is a major challenge to the possibility of State-level legalization experiments. More research is needed to define and explain these challenges in order to reconcile local and State policies.

The purpose of this analysis is to map out County-level differences in receptiveness to I-502 production, processing and retail businesses based on data sourced from publicly available information supplied by the Washington State Liquor Control Board; and research conducted by the WSLCB initial consulting group BOTEC in 2013. These differences appear as a spectrum on which we have identified “facilitative” County environments on one end, and “obstructive” County environments on the other.

While obstructive environments are not surprising in counties that voted against I-502, the development of obstructive environments in counties that voted for I-502 make clear that State level legalization creates a new and dynamic policy landscape that is continuous with, rather than an end to, prohibition as public policy.

We begin by mapping that landscape as a county-level state overview. Counties were ranked on a scale of “facilitative” to “obstructive” based on WSLCB Applicant data from 10/21/2014, color-coded and mapped. Counties were also categorized by their relative voter approval rate of I-502 in 2012. Then we focus these metrics down to Snohomish County to situate their recent “emergency moratorium” in relationship with their rank of obstructiveness. We conclude by discussing the relationship between minority voter mobilization and county-level obstructive environments, and recommend further geographical research along these lines in order to clarify the landscape of I-502 implementation going forward for policymakers and the public.

Washington State Overview

Using LCB license approval data, we ranked each County on the percentages of its allocated retail licenses, producer license applications, and processor license applications that had been approved through Oct 21. For each type of license, the highest percent approval rate was ranked as “1”, and the lowest was ranked “36”. The three rankings for each County were then averaged, yielding a single overall ranking metric (ranging in value from 1 – 36), with lower numbers corresponding to Counties with relatively HIGHER rates of license approval. These are mapped below as Figure 1.

Figure 1: Facilitative and Obstructive County I-502 Environments in Washington State with “Average License Approval Ranking”

Table 1 for Figure 1 MAP

County facilitation or obstruction of I-502 business permitting does not necessarily correspond with voter support for I-502 and, hence, recorded electoral support for legal cannabis as a State policy, due to political and economic variables that have developed since its approval. These include the institution and removal of moratoria and locational and/or permitting restrictions imposed locally that go above and beyond those required by the State.

What we are interested in here is not simply the identification of obstructive and facilitative County environments, but the identification of cases where such environments do not match with recorded voter support or opposition to I-502. In Counties where the degree of facilitation or obstruction of I-502 implementation does not correspond with recorded voter positions for or against I-502, we take this to be an indicator of a lack of representative local Government — or at least a deficit of local democracy.

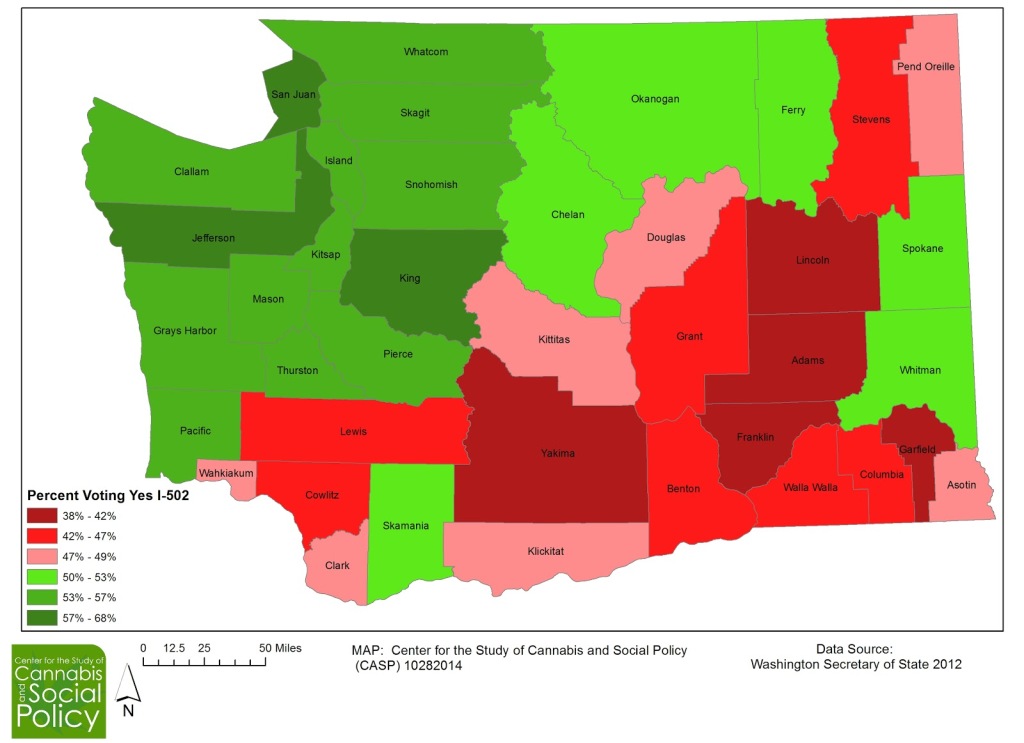

The percent of voters in each County voting for the establishment of a legal cannabis market in Washington State in 2013 was categorized into differing degrees of PRO and CON, and mapped below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Percentage of Voter Approval for I-502 by County

Twenty-four Washington Counties held a clear PRO (>53% for) or CON (>53% against) voter position on I-502. In the breakdown of these Counties below, those displaying patterns suggestive of non-representative local government have been bold-faced.

Of the 9 clearly CON I-502 Counties, 5 have displayed license approval rates that suggest the expected obstructive environments (Adams, Franklin, Lewis, Walla Walla, and Yakima), while 4 appear to have unexpected facilitative environments (Benton, Cowlitz, Grant, and Stevens).

Of the 15 clearly PRO I-502 Counties, 13 have displayed license approval rates that suggest unexpected obstructive environments (Clallam, Grays Harbor, Island, Jefferson, King, Kitsap, Mason, Pacific, Pierce, Skagit, Skamania, Snohomish, and Thurston), while 2 appear to have the expected facilitative environments (San Juan, Whatcom).

With the Washington State midterm election underway, it may be prudent for the voters of these Counties to question their local candidates as to why the results of local I-502 implementation are inconsistent with the message they sent in their vote for (or against) I-502. Such a disconnect is clear in our case study, Snohomish County.

Snohomish County Case Study

After almost 11 months of explicitly allowing I-502 businesses in defined zones, earlier this month, the Snohomish County Council passed Emergency Ordinance 14-086, a six month moratorium prohibiting new producer or processor businesses from opening in the R-5 zone and prohibiting I-502 retail businesses in the Clearview CRC zone. R-5 in Snohomish County is RURAL-5 and generally allows most types of commercial activity in an effort to allow people to “live off of their land”. Cottage industry, especially associated with agricultural activity, is generally permitted in R-5 zoned property, and the stated intent of this zone is “to maintain rural character in areas that lack urban services”. The action was catalyzed by the organizing efforts of local citizens spearheaded by an anti-retail group called No Operational Pot Enterprises (NOPE). NOPE represents a minority interest relative to the County’s substantial pro-502 vote, but their initiative took place in the context of an already obstructive County permitting environment.

Using LCB license approval data, and ranking each County on the percentages of its allocated retail licenses, producer license applications, and processor license applications that had been approved through Oct 21, Snohomish County ranked 21st of 36 Counties in the percentage of I-502 processor licenses granted (at 7.0%), 23rd in the percentage of I-502 processor licenses granted (at 8.9%), and 22nd in the percentage of I-502 retail licenses granted (at 11.4%).

As an example of apparently obstructive and non-representational local Government, Snohomish County had a majority of its voters vote for I-502 (54.6%, ranking as the 11th highest PRO I-502 County) yet appears to have an environment that is obstructing the implementation of I-502 licensing (ranking 23rd in relative I-502 license approval rates out of the 36 Counties analyzed). In spite of this low license approval rate, the Snohomish County Council recently passed the emergency moratorium further restricting the categories of zoning available to I-502 businesses.

The following graph denotes the percentage of the State represented by Snohomish County on a number of variables relevant to not only marijuana, but also to alcohol. We do this to point out that Snohomish County’s obstructionist environment seems to cover more than just one class of intoxicants.

Figure 3 Snohomish Indicators

Data in Figure 3 is sourced from the following links:

http://www.liq.wa.gov/records/frequently-requested-lists

While Snohomish County comprises 10.6% of the population of WA State (and 11.2% of “Estimated Potential Marijuana Users”), it was relatively under-served by State-run Liquor Stores in 2012 (having only 7.5% of them), and continues to be relatively under-served by both current off-premises liquor licenses (at 9.2%) and by Medical Marijuana Access Points (at 7.3%). For whatever reason, Snohomish County residents are being denied their “fair share” of alcohol and Medical Marijuana access points.

The 10.5% allocation of the State’s I-502 retail stores to Snohomish County is in line with the County’s population (and estimated potential marijuana-using population), suggesting that the State has done a good job of allocating I-502 Retail stores in a way that should provide equal access to such establishments across the State. However, the fact that Snohomish County has only 6.2% of the licensed Retail I-502 retail stores implies that the rate of successful licensure has been lower in Snohomish County than in the rest of the State. In spite of these facts, the Snohomish County Council declared an acute emergency, in part because of their perception that their County was being “flooded by applicants”.

The fact that only 8.9% of producer and processor applications in the State fall within Snohomish County suggests that its population stands to be relatively under-served if I-502 applicants within the County were to be granted licenses at a rate consistent with the rest of the State. However, the fact that only 6.6% of the licensed Producer applications and 7.4% of the licensed Processor applications in the State fall within Snohomish County is again reflective of the relative difficulties of reaching a successful licensure within Snohomish County.

In spite of the apparently obstructive environment existing in Snohomish County, 12.3% of the State’s total I-502 Sales (from producers, processors, and retailers) through September have been generated in this County. This suggests a pent-up demand within the County that is not being served well by an obstructive local environment. It also suggests that the few I-502 retail stores that have been able to open in Snohomish County are generating approximately twice the per-store revenue of those in the rest of the State, and are therefore unintended beneficiaries of the moratorium.

The obstructive environment in Snohomish County has benefitted two groups: those who would have the implementation of I-502 obstructed, and those who are currently producing, processing, and retailing under I-502 within Snohomish County. For potential beneficiaries of I-502 such as consumers hoping to gain from an available legal, regulated supply of cannabis and applicants that have invested capital in Snohomish County facilities that are now disallowed, the costs of such non-representative Government can be huge.

Conclusion

This analysis should help readers understand that the policy landscape of I-502 is both uneven and dynamic/unstable for County-level reasons, not simply because of State policy or WSLCB implementation. That said, the slow pace of license approval has allowed time for counter-organizing to occur with few vested stakeholders, even though many I-502 applicants are well into the process of building out and attempting to get licensed. City councils that were already inclined towards caution are being confronted by organized constituents who are fearful and angry.

Our Snohomish County case study reveals not only a counterintuitive obstructive local policy environment, but a trajectory towards MORE obstruction exemplified by an emergency moratorium that does not reflect the reality that implementation is already moving more slowly than expected, given voter support for I-502. The obstructive moratorium is specific to rural (R-5) production and processing and I-502 retail in the Clearview Rural Commercial zone, rather than general to all I-502 business. This creates a policy landscape that is unfavorable to smaller producers that were supposed to be enfranchised by the State Tier system.

The particular local politics driving Snohomish County obstructiveness clearly reflect the mobilization of organized citizens groups that may support legal cannabis as State policy – just not in their backyards. Local citizens (voters) are, themselves, part of the obstructive environment. It is not just City or County councils acting independently of citizen input. The struggle to smoothly implement I-502 throughout Washington State is something that any PRO-I-502 constituents should be actively supporting. Reaching out to and educating your neighbors, the neighbors of your planned facility, and the leadership and others that will be supporting your business (fire, safety, utility, potential suppliers, etc) is increasingly important in the face of a growing (and increasingly effective) ANTI-I-502 (or at least ANTI-I-502 in my back yard) constituency. Ignorance is the primary driver of fear, and ignorance is easily fixed with factual information and the building of trust.

In conclusion, whille I-502 legal cannabis is permissible to voters as a Statewide policy, it may not be permittable by local jurisdictions responding to organized citizens who don’t want it in their backyards. If this obstructive trend continues, it will create a patchwork of permittable landscapes across the State that will constitute an uneven geographic distribution of legal cannabis that was neither anticipated nor desired by the architects and implementers of I-502 as a Statewide policy experiment in cannabis legalization.

A close reading of Seattle Times “Editorial: Where’s the weed? In Seattle, it’s in medical-marijuana dispensaries”

by Dominic Corva, Executive Director

Two days ago the Seattle Times Editorial Board published an opinion that is dangerously disconnected from reality and basic logic. It reminded me of student papers I used to read and comment on at length, sentence by sentence. So I thought I would apply that methodology to the essay: my comments in between each of their paragraphs are in red, below. The disconnection from reality is dangerous because it demonstrates a total lack of understanding of how cannabis markets work, on the one hand; and the complex realities of I-502 implementation on the other. In so doing it throws a political firebomb to the public, suggesting that the public should be outraged and that their anger should be directed against medical cannabis so that legislators can operate as though there is a crisis to be addressed. This crisis frame has no place in Washington State’s efforts to set a global example for creating a peaceful transition away from the failed drug war approach implicated in the ST Editorial voice below.

**********

FOUR months into Washington’s era of legal marijuana stores, a strange reality has settled over Seattle: The city doesn’t seem to care much about the availability of over-the-counter pot.

This is a pretty broad assertion. What do you mean by “care”? One can care a lot but not do anything; one can care little but do something. The implication seems to be that the availability of over-the-counter pot, as opposed to say farmer to consumer transactions, is a serious social problem. Let’s see the argument …

Combined sales at Seattle’s recreational marijuana stores trail those in Vancouver, Spokane and even Bellingham. On a per capita basis, Seattle’s sales are about half of Yakima’s and one-third of Tacoma’s, according to data from the state Liquor Control Board.

Okay, comparative geography in which “retail sales per capita” are presented as evidence of the serious social problem. The data offer other clarifying comparative geographies: King county has 7 approved retail stores, for 2 million residents, while Spokane has 6 approved retail stores for under half a million residents. Pierce county has 7 approved retail stores for a little over 800,000 residents. This explains the “per capita” discrepancy pretty well.

That’s partly due to the glitchy launch of the recreational market created by Initiative 502. Supply problems have led to sky-high prices and late-opening stores.

This is an implicit critique of the Washington State Liquor Control Board, the body charged with implementing I 502. Let’s be explicit: supply problems are primarily the direct result of the slowness of the approval process and the WSLCB’s decision back in February to cut maximum Tier canopy by 30%. These problems are compounded by a host of challenges totally unrelated to the approval process, including local jurisdictional permitting processes that are more stringent than those associated with the WSLCB. They also include local pushback in other forms, such as the current lawsuit against one of the four Seattle retail stores that are open, by a neighborhood church. Retail stores face nearly impossible geographic restrictions that keep other approved retail stores from opening because they can’t find a cooperative landlord in an approved location. Characterizing these factors as “glitches” that are “partly” responsible brushes aside the enormity of their significance, in favor of another explanation …

But the regional sales disparity defies logical and market forces. Does Spokane really have a closet habit nine times stronger than Seattle’s?

Say what? That disparity is easily explained by both decentralized political logic and market forces. And what is a “closet habit”? Perhaps one that isn’t related to Seattle as the historic state center of per capita consumption of mostly indoor, urban marijuana production? and how is that question not a serious one, as opposed to a sarcastic one?

No. In reality, Seattle marijuana users shun recreational stores because they’re getting the cannabis from a larger, cheaper and unregulated source: medical-marijuana dispensaries.

You have not supported your rhetorical answer to the sarcastic question. Then you make an assertion completely disconnected from reality. Right now over 300 medical access points serve Seattle/King county. If all of these were shut down today, how would 4 open retail stores be able to serve the thousands of consumers demanding way more product than those stores could possibly put on the shelves? More to the point, would consumers say shucks, guess I have to go to a 502 store, or would they tap into their social networks to access cannabis from the several thousand growers in the county that currently supply medical access points? The assumption that consumers don’t know how to get cannabis otherwise is seriously disconnected from reality.

As Seattle’s former U.S. Attorney Jenny Durkan warned last month, medical marijuana is “not a loophole. It is the market.”

Was that a warning, or a statement of Federal perspective, or both? If this sweeping, evidence-free assertion were true and not a political statement in a larger agenda, what again is the major social problem? In a complaint-driven policy environment, it is conspicuous that no evidence is being compiled as to the social harm piling up in the city of Seattle.

She’s right. For that, blame the state Legislature.

Why is she right? Where is the evidence? And ok, let’s see the case you must be about to build against the State Legislature …

How big the medical market is remains a mystery. Regulation of medical marijuana is so lax no one can measure it. No one knows how many dispensaries operate or how many customers there are, let alone how sick those patients really are. Yet, storefront green crosses are as ubiquitous as Starbucks.

Hmmm, you would think Jenny Durkan might have a word about how mysterious it is, given that she was just quoted asserting that medical marijuana is the market. One would need to know how big the market is in order to back up that assertion. Perhaps she should have said “We have no idea how big the black market is, but we are pretty sure it’s there’s nothing more to it than the medical market.”

Buyers pay no excise taxes on medical marijuana, so cannabis prices are lower than at recreational stores. “Green cards” needed to gain entry to dispensaries continue to be glibly handed out for as little as $50.

Medical cannabis prices are continuous with what they were before I-502 production and therefore excise taxes came into existence. There are many access points and lots of production, as opposed to I-502 which has very few access points and very little supply, which means even before excise taxes prices are higher. The excise taxes are much higher than they will be in Oregon, so perhaps some of the problem should be associated with how high the excise taxes are.

“Green cards” — medical authorizations — continue to be “glibly” “handed out” for $50 where? Please let patients know so they can stop paying $100-$125 for them. What does “glibly” have to do with anything, other than to smear the alleged motivations of doctors and nurses who are overseen by the Department of Health, not the legislature nor the WSLCB? And “handed out” implies that the process is easy peasy, rather than requiring medical records and an examination per the reality of the process.

This makes a mockery of the state’s landmark new approach to marijuana. Instead of sticking to the strict regime of I-502 — regulating and taxing marijuana, limiting sales to adults and investing in prevention — inaction has allowed the shadow medical market to thrive.

Which “this” makes a mockery of the “strict regime of I-502”? The landmarky-ness of the I-502 approach is that it is designed to operate on its own, no diversion into or out of or cross over in any way with medical markets, unlike Colorado where medical and legal are sold in the same stores. Further, by WSLCB policy, it was designed to capture at maximum capacity 25% of the actual state cannabis market. Production capability right now is at approximately 800,000 square feet of the 8.5 million square feet of canopy that would constitute maximum capacity. About one sixth — 60 out of 334 — of the alotted retail stores are open, many of these irregularly due to supply chain issues. The state favors a gradual approach to implementation, partly because the WSLCB does not have the necessary human resources to inspect and approve it all in a timely fashion.

The medical market was thriving long before I-502, and the black market was too. The latter will thrive until federal descheduling and there’s nothing the state can do about that. And I am not sure why the medical market is being described as “shadow”: a shadow of what? the black market? and clearly it’s not “in the shadows” given the editorial’s reality-based observation that you can see it pretty clearly.

The Seattle City Council put a moratorium on new medical-marijuana businesses, effective November 2013. New storefronts had to become recreational shops, or comply with new regulations expected from the Legislature in 2014.

OK, good empirical facts!

But the Legislature failed — a good bipartisan proposal was tripped up over minor tax squabbling. The cost of that failure is mounting.

The first part of this, good empirical observation! The second part of it: what cost? what is the cost of not driving medical consumers back into black markets given that I-502 alternatives are just taking shape and probably won’t be fully up for another year?

When lawmakers reconvene in January, that legislation should be a priority — and not just for the tax revenue it would churn. The goal must be to serve legitimate patients, limit youth access and build a prevention campaign similar to one that beat down rates of teen tobacco use.

What evidence do you have that it is not in fact a priority? Initiatives for shaping that legislation are going full-throttle, I can barely keep up with the different interest groups that are mobilizing for it. “not just for the tax revenue” seems to be thrown in there lest the reader think that the “cost” referred to above is revenue that isn’t going to the state, or to (barely operational) I-502 businesses. In what world does the suggestion that medical access points be closed down immediately serve the interests of legitimate patients, and where is your study that tells us what percentage of these are being served at all, much less adequately, by currently existing medical access points? Where is the evidence that youth access is expanding due to medical access points? What do teen rates of tobacco use have to do with teen rates of cannabis use?

Meantime, Seattle, which has been allergic to policing even the bad actors in medical marijuana, recently sent letters to 331 cannabis-related businesses, reminding those that opened after November that they were “in violation of city law.” City Attorney Pete Holmes’ office has sued five medical-marijuana businesses for failing to follow basic zoning and building codes.

Where is the evidence that Seattle hasn’t been policing bad actors? Your second sentence contradicts your first sentence.

The world is watching Washington’s grand experiment with legalization. In the state’s biggest city, the experiment is being run over by the ubiquitous green crosses.

You have not provided any reality-based evidence that medical cannabis markets are squeezing out 502 cannabis markets. The reality is that until supply chain issues smooth out, prices come down, retail stores open, and retail stores stop runnning out of product, medical access points are not competing with legal retail for customers. They can’t compete with something that doesn’t substantially exist yet.

Editorial board members are editorial page editor Kate Riley, Frank A. Blethen, Ryan Blethen, Jonathan Martin, Thanh Tan, Blanca Torres, Robert J. Vickers, William K. Blethen (emeritus) and Robert C. Blethen (emeritus)

I-502 Rural residential producers correlate with rising property values; question “emergency” nature of moratorium

by Dominic Corva, Executive Director

Our strategic partner, Washington Bud Company’s Shawn Denae, is leading the struggle to reverse Snohomish County’s emergency moratorium, and has been gathering evidence to demonstrate the positive economic impact of rural residential I-502 license applicants in the County.

She writes, “I searched for property values trends in Sno Co in R5 heavy zip codes. Results prove that values have increased double digits since the passing of R5 zones for MJ farming: Read More: