https://soundcloud.com/cannabisreport/cannabis-consciousness-21-dr-dominic-corva

by Dominic Corva, Executive Director

TRANSCRIPT BELOW

“Dr. Dominic Corva of the Seattle-based think tank Cannabis and Social Policy recently visited Southern Humboldt and talked with CCN’s Kerry Reynolds about lessons for California in legalization trends in Washington and Oregon.”

This is Cannabis Consciousness News produced at Redwood Community Radio in Redway, California. I am Kerry Reynolds reporting for CCN.

Kerry: This is Kerry Reynolds with CCN. I’m here with Dr. Dominic Corva of the Cannabis and Social Policy Center, based in Seattle, Washington, correct?

Dominic: That’s correct.

Kerry: In terms of enforcement in cracking down on the black market, trying to pursued people into the above-the-ground market, are there any things you are seeing in Washington, in terms of cracking down more on the black market?

Dominic: So, you know, the black market needs to be defined, right? We all assume we know sort of what the black market is but it’s also a term that gets used pejoratively to identify like mad people, as opposed to — the black market, you know, technically is, you know, the informal market essentially like un-taxed, un-regulated market. So, the main thing you know in Washington that I suppose could be learned is that you really need to make sure that you’ve got plenty of retail outlets. That is — you can have all of the best intentions and all the best designs for permitting growers but if their product doesn’t have a place to go, if there is a bottleneck because there is not enough retail stores then, you know, like you are looking at diversion from a, you know, regulated system.

Kerry: Yeah, then it’s going to be filled out at someone’s apartment.

Dominic: Yeah, so that’s — the distribution question needs to be worked out and whether that means necessarily like, you know, opening up retail permitting or coming up with farmer-to-consumer distribution, there are lot of different ways to I think create pathways to market from the field and California should consider all of them _____1:50 basically because it grows way more than California consumes and in that way it’s like Oregon, but on a much bigger scale, although I’m not sure how much bigger scale these days Oregon is. There is a whole bunch of Californians in Oregon that are applying the lessons that they have learned.

Kerry: So, things are blowing up basically?

Dominic: Things are blowing up in Oregon. You know, Oregon’s got the cheapest cannabis in the country now according to the latest map that came out of Cannabis Prices, and, you know, historically that’s the indicator of like, you know, where most of it’s coming from. Of course, Oregon being right next to Northern California, it’s really — they should break it by county because it won’t be the whole state that will be cheaper. It will be like, you know, that zone from the Bay area up to — that’s really, you know, a cannabis growing region that’s continuous.

In terms of certifying, you know, gardens as, you know, they have got their water permit and so forth, you know, the question is that, okay, let’s do that so that you know, we can get the environmental stewardship going, but on the other hand if you try to apply like a seed-to-sale tracking system in this area, you are throwing it all out the window because there is just too much products and it needs to go somewhere and they can’t all go into California, they just can’t; it’s not mathematically possible. I think it should be interesting to see how that aspect of formalization happens in this area where, you know, attempts to shove people into a box that really like, you know, makes their lives too difficult and makes them not want to participate, gets kind of back to its first problem, which is like nobody wants participating from here because it doesn’t work with them.

So, there is going to be particularities to the area that’s going to be a little tough to work out in a nuance fashion at the state level, so I’m really hoping that — and it definitely seems to be the case the local government is much more interested in being involved in that. Humboldt, you know, obviously had its head in the sand for a very long time just like everybody else. I think that’s really, you know, one of the interesting things about Kevin using that all. Kevin is like, that’s not head in the sand, that’s head out of the sand and actually looking around 360. So, that’s promising to me. It’s promising to me. I think it’s easier to make sensible policy with people that like you’ve met face to face, you looked in the eye and you’ve talked to them and they talked to you.

Kerry: It was startling as someone who covers the industry here to see Representative Huffman, meeting with people that were out-cannabis farmers just recently and I believe Senator McGuire as well.

Dominic: Yeah, that’s right.

Kerry: So, to have Luke Bruner, representative of California Cannabis Voice Humboldt, sitting at the same panel table with the Lieutenant Governor was really showing how much the cannabis producing community has gained respect in order — and legitimacy in a way before the full legality has come onboard.

Dominic: Absolutely. You know, I think that the politicians are responding to the organizing. They understand it’s — Hezekiah, obviously, was also at that table. Hezekiah Allen.

Kerry: Yes, in their early meeting. I really think — and in a public meeting I was like, yeah.

Dominic: Went to public meeting, that’s right.

Kerry: But Hezekiah Allen of Emerald Growers Association, also representing cannabis farmer.

Dominic: They are at the table and like that’s the first step. It is like sitting down at the same table.

Kerry: And even John Corbett, the Chair of the North Coast Regional Water Quality Board sat at that meeting. When we go to do our water inspections, we don’t check for 215s and we don’t care if it’s medical cannabis or just cannabis. So, there is sort of our recognition of reality on…

Dominic: There is progress — there is real progress being made; just so much progress being made on dealing with what is actually there instead of what you wish was there or not there. You asked me about, you know, lessons from Washington and Oregon. Did you want to, you know, talk about the elephant in the room which is the tendency that Oregon has at least now kind of confirmed for legal cannabis to be an occasion to radically change, you know, essentially medical cannabis?

Kerry: Are the dispensaries of California going to go the same way as the dispensaries in Washington and by the way, what’s happening with the dispensaries in Washington?

Dominic: Yeah. So, basically what’s happening with dispensaries in Washington is there is Senate bill they just passed 505(2), that was essentially sort of a comprehensive medical marijuana, you know, regulation act and if you will recall back in 2011 we had one of those. And it established a system for, you know, regulating commercial, you know, medical dispensaries and our governor section vetoed every part of it that had to do with regulation.

Kerry: The Washington Governor.

Dominic: Washington Governor basically because any part that would have involved a government official like, you know, being a part of that regulatory process — what she said then was, subject to them to Federal prosecution and so section vetoed out, you know, every part of it that would have been regulation. And so all the folks who were geared up to, you know, satisfy the regulatory conditions in that bill which came from legislature and not initiative, they know what to do and so they got the legal advice that pretty much became standard practice which was, to operate as collective gardens and there was collective garden language and of course, collective gardens in that bill did not have to be regulated. They were non-commercial provisions. They were appendages to the actual regulatory structure which involved commercial regulation.

So, what we have is essentially excess point system that was — that sprang up not overnight at all, but certainly under the new conditions basically, if you’re a collective garden them you weren’t regulated, so it’s really easy to open up. All you got to do is find a spot in the strip mall. That’s the — that was the legal interpretation that they were operating under for four years and until the cannabis decision from last year, which was the first like — sort of challenged, that actually was ironically brought by medical cannabis activists to essentially get a legal opinion that, in fact, excess points were legal in the State of Washington and of course, they got the opposite result. And since then basically like all anyone has had to do was apply that decision wherever they were and if they want to, you know, basically declare medical marijuana illegal, and that’s essentially what happened.

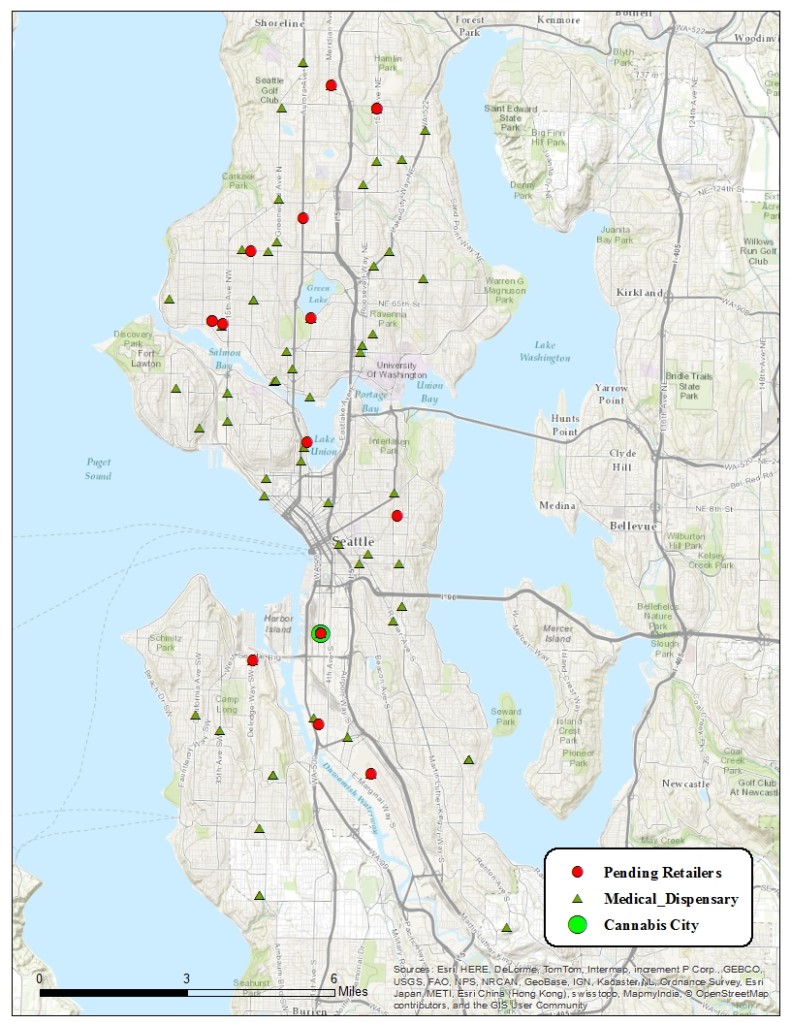

So, with 505(2), it creates a medical aspect to the legal cannabis markets. I don’t want to go too deep into those. I think we have talked about that a lot before, but what’s happened to the existing dispensaries is that City of Seattle is now kind of leading the way in terms of a specific framework for it, because technically everybody’s got till July of 2016 to be open. City of Seattle issued essentially a three-tiered process for dealing with all of the dispensaries within its jurisdiction. So, the first tier is essentially, if you opened up your dispensary after January 1st, 2013, you are out. So, you are regarded as a, you know, as an opportunist. You are just showing your lack of good faith because you opened up after legal cannabis passed. So, that’s a condition.

The second condition and that’s one — this one was unanticipated I think and a little bit surprising to folks, is that the laws for legal cannabis which are only for people 21 and over, just got applied to dispensaries. So, dispensaries basically were now being investigated every time they sold to a patient that was under the age of 21; that’s ongoing. And so as a result the dispensaries and dispensary system — any patient that they had that was under 21 which, let’s say, was a fair amount actually — a lot of their clients are…

Kerry: Children with epilepsy, for example.

Dominic: Yes. But children with epilepsy were not coming and buying, you know, _____9:50 on a regular basis necessarily at the dispensaries. But there is a current way in which actually people under the age of 21 can go to a dispensary and wouldn’t get the dispensary in trouble and that’s if they got essentially like a caregiver letter. Now, under the new system basically which, you know, again it will take a while to kind of implement it, instead of collective gardens there are four-person cooperatives that you can register with the State, and I think it’s three plants per person so, like you know four times three is twelve.

So, the new legality is, you know, one that is radically different from what was going on already, which makes it a pragmatic policy because what it’s doing is actually not really like working with what’s there and trying to shift it, it’s denying what’s there and burying your head in the sand and just saying, just go back to the black market basically. So, that’s the interesting dynamic that’s going on right now and Washington’s dispensaries even if they are not shutdown because they are all getting letters in there — if they don’t shut down then they get like a huge fine and the other conditions are they have to be, you know, paid up on their taxes.

Kerry: How many dispensaries are we talking about here in Washington who are now illegal and being told to shut down because of this…

Dominic: Well, they are being told not necessarily to shut down unless they have — they meet their prior conditions already like you say — again, if they have not been paying their taxes, there is your letter you should shut down. You have been paying their taxes, you were open before January.2013, we are going to leave you alone and also you now get to apply to be part of the rec system. And let me say that the mathematics of this are not as severe as you would expect. The City of Seattle counted something like a 106 dispensaries within its city limits and identified that about half of them actually have been open before January 1st, 2013. So, like for their first cut half of them were still surviving as eligible to continue as part of the system. Now, of course, then they are going to have to meet, you know, the zoning requirements and all the other things.

So, like how many of those people actually end up in the rec system, not sure, but again this is the good actor, bad actor, you know, a discourse. It’s like let’s identify the good actors and then _____11:55. Everyone else is a bad actor and has to go away except for that’s not how it’s ever worked within the context because really more people will just go away, they find other ways to do business. So, what’s happening essentially is our, you know, not terribly regulated medical system in Washington is being actively downsized and dramatically changed.

Kerry: And at the same time production is increasing.

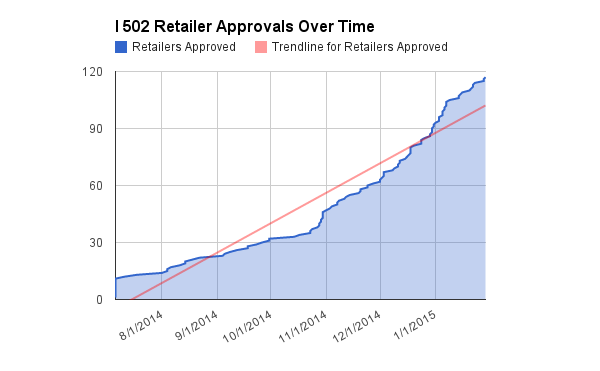

Dominic: Yeah, so the production side of things — of course, the rec side of things especially that’s an issue because Washington has never been obviously a big producing State. It’s been, you know, an indoor producing State and importer of you know Oregon, BC and California cannabis. But with the 502 system of course like that’s a native production, you know, system and that system we are getting up to about 800 pounds a month indoor basically. It seems to be moving through the inventory. Our outdoor season last year on a very abbreviated one again, you know, 14,000 pounds and created within the i-502 market, you know, a gloat and a problem with prices and so forth because we had 80 retail stores open in December. We have like a 150 open now. We are on schedule to have about 250 open in December of this year.

So, not even the full component of 335 that like the state has authorized there to be for a number of reasons, bans, inventory and so forth. But what that says to me is that you got twice as many retail stores. Let’s be generous and call that three times as many retail stores. You are going to have at least 10 times the production. So, what does that say for, you know, the outlets and the prospects of, you know, diversion or of folks who may even be actual growers who are growing buds but are not able to sell their stuff because there is not enough retail outlets essentially for it. It’s a chokepoint.

So, this is all happening of course in the context of downsizing the medical dispensaries and so fewer medical dispensaries, not enough retail dispensaries, lots of production on legal side, plenty of production around in Washington State, I mean that’s legal side. All that is recipe for, you know, what the state says it doesn’t want which is diversion in the black market.

Kerry: And it’s what the Department of Justice says, it doesn’t want through the Cole Memo.

Dominic: But that’s the funny thing about the Cole Memo. The Cole Memo is actually relatively broad or vague and when it comes to talking about diversion and the conditions under which the legal experiment can go forward which is — which folks interpreted additionally, diversion meant out of the legal market into any other part, whether that meant out of the state, in the state. If it was produced in the legal market, it needed to be sold in the legal market.

So, diversion was interpreted as being just about legal cannabis. Since then diversion has been now applied to include essentially medical cannabis and so, medical cannabis is considered to be, you know, black market or diverted. You know, if you don’t have a system regulation, it’s all diversion. Diversion is the condition of not regulation according to the sort of latest popular sort of interpretation, which is why, you know, part of the justification for shutting down medical system is because Cole Memo. And the Cole Memo, again, originally like did not at all apply to medical. Why would you ask the states to be home to a standard that the Federal Government has never been able to actually keep itself, which is shutting down the black market.

If we interpret the Cole Memo to include that kind of demand, what we are doing is essentially saying the Cole Memo, you know, is absurd on its face and, you know, like how we are supposed to take it seriously at all. If it sets an impossible condition and you are interpreting that impossible condition as something you have to meet even though you can’t, it would be totally impossible and you don’t have the funding to do it, it’s taking steps backward Kerry. So, for me that’s a concern in Washington State.

It’s not like I’m here to defend, you know, unregulated or deregulated cannabis; I’m for regulated cannabis. I’m for evidence-based regulation though. You know, evidence that this works and that by the way is also part of the Cole Memo. It has to actually work. That’s a condition.

Kerry: Robust regulation.

Dominic: Robust regulation, which is interpreted as regulation that actually like does what it’s supposed to do and that’s not a reinterpretation of the Cole Memo. That’s an original interpretation of the Cole Memo and it still applies and I believe that, you know, our legislature has fallen down you know, on their faces when they are ignoring — they are ignoring that part of the Cole Memo. Cole Memo says it’s got work. They are doing stuff that’s the opposite essentially and I feel like…

Kerry: Probably not their intention to do it.

Dominic: Yeah, probably not.

Kerry: So, we have got a long — we have got a lot of issues in Washington and I think you have given us a real good overview of that. I know you have also been doing more analysis of the Oregon recreational market. What’s the status today in Oregon, please?

Dominic: Well, what’s happening in Oregon is that’s — although Oregon had a regulatory system, you know, the Oregon Medical Marijuana Act, they were cruising along after initiative passed, there was a joint taskforce, you know, bipartisan, you know, both members of the _____17:14, and what they were tasked to do is writing rules to create the legal market and it had nothing to do with medical, nothing. Somewhere along the way that joint taskforce essentially stumbled over, I think increasingly like the fact that it wasn’t addressing medical and essentially dissolved and we are left now, instead of the joint taskforce that actually has been listening and trying to figure things out, we are now seeing in Oregon the position of an agenda that looks a lot like Washington’s. It’s an agenda that claims that Oregon needs to be concerned about the Cole Memo’s diversion situation. Again, the diversion thing is really — it’s getting hammered home as a common sense discourse and is being redefined in my opinion.

Kerry: By whom? Who is doing this?

Dominic: Well — so, you know, it’s usually hard to tell but you know we do have a white paper that was produced by a Privateer Holdings Incorporated, same folks who own Leafly. They are an investment group. They are based out of Seattle. They have run Tilray, a big cannabis warehouse in British Columbia and, you know, they are essentially venture capital firm that invests, you know, in and around the cannabis industry. Now, what this really means right now is that, you know, they invest in real estate, they invest in things like Leafly, you know, really safe things or you know what…

Kerry: Things that are directly touching…

Dominic: Right.

Kerry: The plan, the dangerous plan.

Dominic: Yeah, except in Canada, right Tilray.

Kerry: Okay, and that’s a producer and seller.

Dominic: So, Tilray is a production facility, so — exactly. So, like they want to get into that. They think very highly of their ability to do so and they think essentially — obviously, what works for the Canadian system is, you know, the fact that it’s a centralized sort of warehouse production predominant system. And that is not the system that works on the West Coast United States because to do that — even if they were able to capture the market that they think they can capture, we don’t need more people growing cannabis here on the West Coast. We have got a lot of people who have been doing it for a while and doing it pretty well. Freezing those people out of the legal regulated market basically by, you know, making it harder and harder for them to meet conditions to be in it, which is — the white paper is very much, you know, there’s a very explicit like a medical market needs to be reigned in and, you know, legal market needs to be _____19:40 them, right said. Centralized warehouse production and so it’s a white paper, right. So, that means it’s for policy makers and it’s like this is your issue in Oregon and this is — but it’s very…

Kerry: But it’s being written by someone it sounds like or an entity that has a very obvious agenda.

Dominic: It has a private interest. Yeah, it’s a really-really naked agenda, you know, like it’s not even pretending. They are basically saying — there is a certain kind of attitude there that’s — it’s a little incomprehensible to me. But that’s public documents and it was meant to guide policy makers and very recently, you know, that’s the direction Oregon policy is going which is to remove protections from medical cannabis growers that currently exist for them, and that’s the key thing.

So, for Oregon — like California, Oregon is a big exporter. You know, Oregon system — the concept of diversion like has to be treated very pragmatically because you cannot mathematically fit Oregon production into an Oregon consumption system. It’s not possible. What you do with everybody else there…

Kerry: Well, come on doctor, if everybody started smoking pot from morning to night maybe.

Dominic: I’m not sure actually. Like — possibly, I don’t know, but certainly…

Kerry: Yeah. Okay, so Oregon is also an exporter?

Dominic: Also, a huge export — so, the question is in terms of the social ecology is that, okay, they are producing a lot of cannabis and they have been doing under the legal protection of Medical Marijuana Act. So, they get X amount of plants and they grow outdoor plants in Southern Oregon and they grow big ones, right. So, the problem is that the protections are being talked about as that’s what they need to take away. So, that would leave these folks without a pathway into the rec system, (a) because they can’t fit into it and (b) kind of leaves them back in the space of vulnerability that they haven’t, you know, had to — they have been able to be integrated members of society in many ways obviously because they have been left alone.

Kerry: So, the celebrated legalization of cannabis in Oregon is now making medical growers in Oregon more illegal.

Dominic: It is — vulnerable, that’s right, yeah. That’s the trajectory right now. It could change next week.

Kerry: So, who would they expect to grow the cannabis in Oregon?

Dominic: Privateer and — Privateer Holdings Incorporated perhaps. Who do they expect to grow? The people who get in on the system basically, who are able to get into the rec system. Again, like those rules are still being sort of written, they are still being hammered out.

Kerry: So, there are no licenses now yet, it’s still in process; sounds like it’s getting pretty butchered from the original voter concept.

Dominic: Absolutely…

Kerry: Spirit of the law.

Dominic: I’m sure that that is the case and so for me it’s very interesting to watch this sort of medical cannabis versus legal cannabis like antagonism develop because it’s framed in a one way and it can’t be framed another. It’s framed as, you know, these people are not worthy citizens because they are all gaming the system anyway. Medical marijuana is a fraud, is the discourse, right and that’s why essentially these things are happening in Washington and Oregon because policy makers have been convinced by someone or someone’s such as Privateer Holdings that medical marijuana is a fraud.

Now, what I understand obviously, you know, all cannabis, especially medical like _____22:56, but on the other hand I understand that _____23:00 doesn’t really fly necessarily to the American public. What I would say, you know, to the American public is that actually, you know, medical marijuana laws are not just about the right to health and therefore about whoever is being fraudulent about claiming that right to do things to make money for example.

It’s also about legal protection from an insane drug war and especially for growers that is the case. Why is it that like — it’s not okay for folks to grow, you know, herbs in their backyard, why is it that we have to track this like it’s nuclear waste instead of an herb. Why is it criminal to grow a plant and to me like — medical marijuana instead of fraudulent I would say that it has been a shield and I think it’s been human right shield for, you know, a more ecologically, you know, in-tune population essentially to carryout direct civil disobedience against an unfair, unjust, racist and genocidal law. The threat to our society has come from the drug war not from, you know, people growing plants.

Kerry: And in the meantime, these people that they are —

Dominic: They need those protections, they need to keep them.

Kerry: They have also been providing the medicine that has been saving children with epilepsy from 200 seizures a day, etc., so that sort of recognition we saw in Garberville because of the organizing in education that’s been done by the grower population here in Northern California. That’s not coalescing as well in Oregon yet, and would have to pretty quickly to reverse this trend would you say?

Dominic: Well, you know, to be honest Oregon is incredibly organized and, you know, they have had _____24:35 in the room like I spoke to the Oregon Sun Growers Guild, you know, last year when they were like, you know, what do we have to expect coming up, you know, I was talking about well, this is the rule making process and Jonathan Mann was in the room _____24:45 and he was like, and this is how it’s going to work in Oregon, you know. He gave the very specific thing. So, they have been there. They have been in the room. They are talking to each other in a way that never was the case in Washington and still this is happening and that’s what scary about it, is that, this is not, you know, defenses population that’s been mobilized against; these were activated citizens who were already calling their, you know, representatives and being very engaged in the process and they are still getting shoved out.

So, it’s difficult to say, you know, like — obviously, I don’t have the answer for you know, how it’s going to be reversed. I’m hoping that by presenting, you know, evidence in the base policy recommendations that I’m hoping that that can help; it didn’t help in Washington, so I don’t know. But, you know, either way the upstart of this is the whole thing is going to move forward one way or the other and it’s either going to be moving forward with, you know, more social antagonism because of the policy that’s been created is going to be less. Either way we are going to have legal cannabis and we are going to have medical cannabis and one shape or form we will have a black market, but the fact is that people are making decisions that are changing the landscape in a way that is potentially, you know, productive of more conflict in society rather than less and that’s my main concern.

Kerry: Thank you for all the work you are doing with Cannabis and Social Policy in Stanford.

Dominic: Thanking you for getting the word out.

Kerry: Cannabisandsocialpolicy.org, correct. Any closing remarks?

Dominic: Yeah, I do actually want to, I want to give a plug for the women’s groups that are starting to proliferate here in Humboldt, CCVH Women’s Group and the Women Grow. There are meetings that happen in Northern Humboldt, meetings happen in Southern Humboldt. This is — honestly, if there is anything I can tell you about Washington that’s really positive is the women’s groups have been, you know, incredible.

Kerry: In Washington?

Dominic: Yeah, they have been, you know, powerful and humane and forces of good and I see that happening here too and I’m really starting…

Kerry: Yeah, Normal Women’s Alliance also. So, we have three different, four different women groups that are really gaining momentum here in the region which is also very promising.

Dominic: I’m really excited about that. I think they will make the difference honestly.

Kerry: Yeah, bringing women to the table always helps the discussion.

Dominic: Yeah, absolutely.

Kerry: All right. Well, thanks Dr. Dominic Corva.

Dominic: Thanks Kerry.

Kerry: Okay.

That’s all for today’s show. Thanks for listening and join me again next week 5:30 p.m. for another special edition of Cannabis Consciousness News. You can also find links to this and past programs on the Facebook page Cannabis Consciousness. Reporting from the heart of the emerald triangle, this is Kerry Reynolds.