by Dr. Michelle Sexton

Traditional medicine (TM) is the generational and societal healing wisdom that has developed sequentially by cultures, prior to the genesis of modern medicine. The World Health Organization defines TM as “the health practices, approaches, knowledge and beliefs incorporating plant, animal and mineral-based medicines, spiritual therapies, manual techniques and exercises, applied singularly or in combination to treat, diagnose and prevent illnesses or maintain well-being.”

The contemporary exploitation of plant compounds, via the chemical revolution and the genesis of synthetic compounds, has culminated in modern chemically-based medicine that is unsustainable, and in many cases with questionable risk:benefit ratios. The United States is in a minority compared to 80% of countries that still primarily use traditional medicine to treat the whole person. Some examples of these ancient approaches include Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, Unani, ancient Iranian medicine, Islamic medicine, traditional Vietnamese medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, and traditional African medicine systems such as Multi and Ifá.

The earliest written records of plant-based medicine or herbal/botanical medicine (sometimes known as “herbals”) from Egyptian, Chinese, Indian and Arabic texts all included Cannabis in their repertory. An Egyptian manuscript known as “Fayyum Medical Book” compiled knowledge dating from 6 BCE and discussed using topical application of an herbal mixture that included Cannabis (sometimes heated) for “curing” of tumors. It appears that Cannabis was often used topically also as “a treatment for the eyes” (Papyrus Ramesseum III, A 26, ca. 1700 BCE.). There are records indicating that it taken internally to treat diarrhea, urinary problems, pain, spasticity, as a vermicide, as a love potion, for impotence, pulmonary congestion, anxiety, as an anti-inflammatory, and possibly to “cure anger and sorrow” (C. H. Oldfather, Diodorus Siculus, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1933, p. 470). The ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist Pedanius Dioscordes referenced hemp in his medical/botanical book “De Materia Medica” (50-70 CE) which is the primary source of historical information on Greek, Roman and other medicines of antiquity. Of hemp, he wrote: “being juiced when it is green is good for the pains of the ears”. Pliny the Elder, who was a Roman naturalist, included hemp in a volume he wrote, Naturalis Historia, (77 CE). Skipping ahead to more modern times, the French writer M. Marcandier reported in 1778 that hemp was reported to be useful in thetreatment of “tumors”. The term “tumor” may have been used to describe any kind of “abscess, sores, ulcers or swelling” but it is unclear if these tumors included what we consider today to be cancerous tumors. Based on these documentations, Cannabis has clearly been an element of TM from the earliest recorded history to more contemporary times.

Dr. William Brooke O’Shaughnessy introduced Cannabis to contemporary western or “modern” medicine, around 1839 when he described successfully treated cases of rheumatism, hydrophobia, cholera, tetanus, and epilepsy he observed at the Medical College of Calcutta. Upon his return to England in 1843, he introduced “Indian Hemp” as “an anti-convulsive remedy of the greatest value.” Western medicine reacted promptly as a wave of cholera was in motion and in France, Dr. Louis Aubert-Roche, successfully used it in treating “the plague”. Hemp had also found its way into Hahnemann’s and otherhomoepathic “material medica” from 1811, where it remains today.

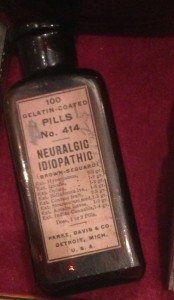

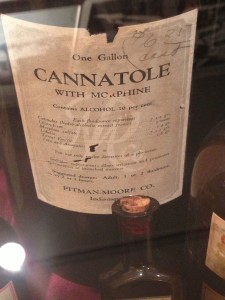

The American Eclectic physicians, an early branch of American medicine that peaked around 1890, relied heavily on botanical use that they drew from the Native Americans. The Eclectics included Cannabis in their materia medicas (the contemporary “herbal” texts) at the turn of the 20th century. The American Materia Medica (1919) by Finley Ellingwood (a major Eclectic practitioner) classified Cannabis as a narcotic. Roberts Bartholow was a more “conventional” American doctor at this time who did the first experiments with electrical stimulation of the brain. He dared to investigate the Eclectic’s claims and classed Cannabis as a “cerebral excitant” (From the Eclectic Medical Gleamer, March 1912 vol.8,2). These opposite effects of being sedative and excitant may demonstrate what modern science would consider biphasic actions of cannabinoids at their receptors. Ellingwood’s text continues: “its mode of

action is sedative, narcotic, anodyne and anti-spasmodic. It acts upon disturbed function of the nervous system”. The monograph goes on to describe therapy for “pain, insomnia, melancholia, hypochondria of the menopause, epilepsy, heart disturbance, functional disorder of the stomach, neuralgic dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia and metorrhagia, gonorrhea, arresting priapism, for genito-urinary infection and impotence, coughs, and laryngeal spasm”. These are some of the documentations of the traditional use of Cannabis as a therapeutic agent. This brief, and in no way comprehensive, historical background is intended to demonstrate the documented ancient history of Cannabis as a TM. These documentations illustrate the efficacy and relative safety of this plant medicine and serve as the historical analog to western medicine’s drug approval process. It is improvident to assign plants to reductionistic scrutiny that single-agent synthetic drugs should be subjected to, as the historical records speak for themselves. Also, the complex and synergistic way that herbs or herbal formulas work alongside other natural and traditional approaches to restore health, are too elaborate to reduce to the current gold standard of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the defining feature of

action is sedative, narcotic, anodyne and anti-spasmodic. It acts upon disturbed function of the nervous system”. The monograph goes on to describe therapy for “pain, insomnia, melancholia, hypochondria of the menopause, epilepsy, heart disturbance, functional disorder of the stomach, neuralgic dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia and metorrhagia, gonorrhea, arresting priapism, for genito-urinary infection and impotence, coughs, and laryngeal spasm”. These are some of the documentations of the traditional use of Cannabis as a therapeutic agent. This brief, and in no way comprehensive, historical background is intended to demonstrate the documented ancient history of Cannabis as a TM. These documentations illustrate the efficacy and relative safety of this plant medicine and serve as the historical analog to western medicine’s drug approval process. It is improvident to assign plants to reductionistic scrutiny that single-agent synthetic drugs should be subjected to, as the historical records speak for themselves. Also, the complex and synergistic way that herbs or herbal formulas work alongside other natural and traditional approaches to restore health, are too elaborate to reduce to the current gold standard of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the defining feature of

chemically-based medicine. However, cannabis in inhaled and oral forms has been subjected to rigorous large RCTs for specific indications such as pain and spasm and has prevailed. There are adequate records to show that humans have known which plants are toxic and deadly, and which are helpful and healing by trial and error over centuries. Plants and human beings are biologically too intertwined for solely viewing their relationship through the impoverished current models that were designed for single agents and a more reductionistic approach to medical treatment and healing.

chemically-based medicine. However, cannabis in inhaled and oral forms has been subjected to rigorous large RCTs for specific indications such as pain and spasm and has prevailed. There are adequate records to show that humans have known which plants are toxic and deadly, and which are helpful and healing by trial and error over centuries. Plants and human beings are biologically too intertwined for solely viewing their relationship through the impoverished current models that were designed for single agents and a more reductionistic approach to medical treatment and healing.

The trial-and-error method, or what might be viewed as “uncontrolled” clinical trials, continue today with a host of plant medicines, while increasingly “We the People” are turning to them for their greater safety profile and history of efficacy. Combine this movement with a return to nurturing our bodies, relationships, communities, societies, cultures and our planet, and there is room for hope of a healthy future. Indeed, there are lessons to be learned from the current phenomenon of cultivating and using Cannabis as a botanical medicine, such as how organic gardens, growing our own medicine, locally, cooperatively, and responsibly is a means to sustainable health. According to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family including, food, clothing, housing and medical care . . .” (Art. 25 Sec.1). May our right to pursue traditional medicine and natural health not be overcome by municipalities, higher governments, capital gain, healthcare plans or other forces that have high social costs and mitigate our larger freedoms to pursue the time-honored means of healing ourselves with plants.

The current awakening to herbs, and specifically Cannabis, for medicine is a portal “back to the garden” of botanical and sustainable medicine that is misconstrued as “alternative” when it is in fact universal and time-honored. Animals and plants are made for each other. We have co-existed from the beginning of time, with plants the servants that provide us food, shelter, clothing and medicine, thus sustaining our survival. Cannabis: the gateway herb.

Its fantastic as your other blog posts :D, regards for posting.