by Dominic Corva, Social Science Research Director

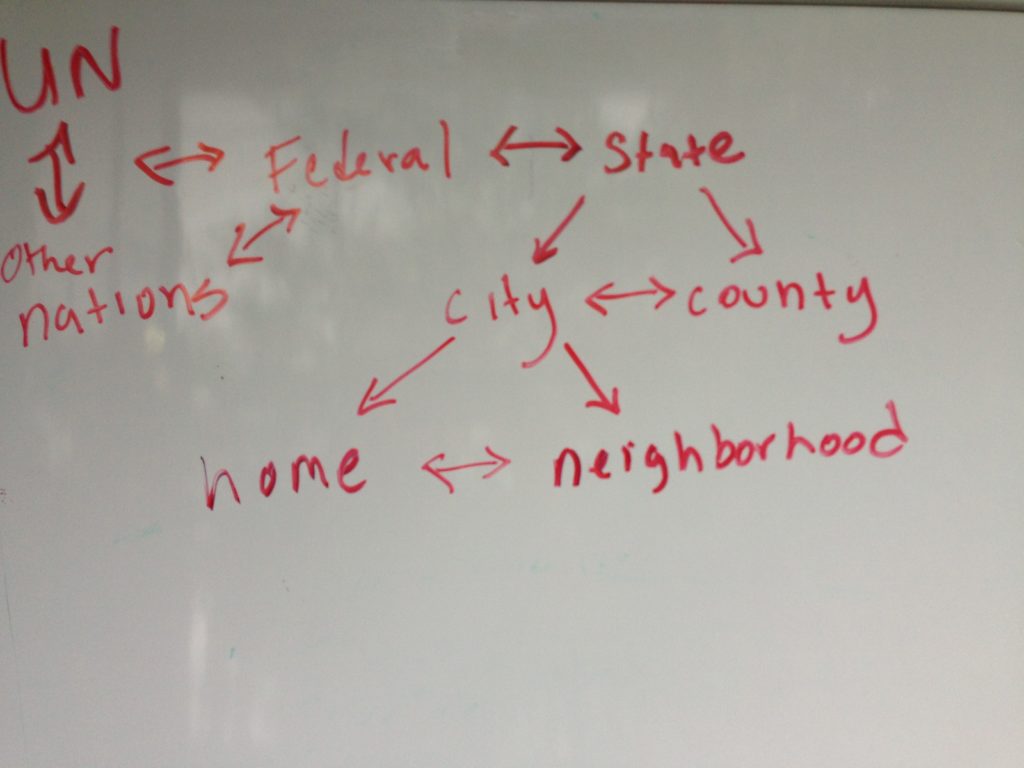

I’ve been using a “policy ecology” metaphor to describe the complex development of national (and global, implicitly) cannabis policy landscapes, and this post’s attention to Federal evolution provides an opportunity to strengthen and clarify that interpretive frame. Please forgive the informality of the whiteboard photo, but today’s post focuses on the “Federal” node and its implications for especially the “Federal-State” relationship. It’s also a helpful reminder that this ecology is a living one, not a fixed or static one, and its dynamics are always evolving even when not in an election year.

Presidential Elections set the stage for actual change, of course, and don’t in and of themselves mean anything. They set the stage because each new administration picks new people for institutional positions, and these people always start from where the institutional position was, not where the new people are. The new people then exert their agenda on the institutions, and, it should be noted, vice versa. The institutional positions through which the president has the power to evolve Federal drug policy is not the DEA chief, but the Attorney General, who heads the Department of Justice. In the Obama Administration, that position was held by Eric Holder and then James Cole.

It should be noted that the President himself (still no women, of course) theoretically can exert more radical change through Executive Order, but those carry much broader political risk and reward calculations. We’ll get to that later in the essay.

It should also be noted that legislative elections also set the stage for actual change, but in the aggregate rather than at the individual level. Individual Congresspeople lead, but their political agendas have to accommodate horse-trading around ALL the other national political issues, of which cannabis policy reform remains pretty minor. We can elaborate but it would take us a bit too afar from the focus of this essay and perhaps will be revisited in a later post.

So, what does a Trump administration mean for cannabis policy landscapes in 2017, and at least the next three years?

Directly, it means that Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions will succeed James Cole as the Attorney General [EDIT: it’s Loretta Lynch, but she continued to implement rather than revise the AG Memo]. Because Donald Trump is not a “normal” Republican President-elect, this AG pick is more than the difference between a Republican AG and a Democrat AG (under a prospective Clinton administration)). Let’s explore the ways.

Trump’s politics, for the election, were “outsider” politics: populist and demagogic, rather than continuous with standard Republican politics. That means he said a lot of things that appealed to the people who elected him, rather than the Republican establishment which he excoriated as part of the swamp he would drain.

Trump’s politics for running the country now that he has been elected, may diverge considerably from the anti-establishmentarian rhetoric established on the campaign trail. This applies to all aspects of national policy development, for which cannabis policy is, again, relatively insignificant. It seems likely he will move forward with some of his anti-establishment populist agenda, while walking back an unknown but perhaps majority share of the rest of it for political and practical reasons.

So we have to pay attention to Trump’s election politics on the one hand, and his probably divergent administrative policy moves, especially his AG selection, to try to figure out whether the cannabis policy landscape will change and how.

His election politics with respect to the DOJ’s area of influence were fairly textbook, for 1968. He used the exact domestic political frame as Richard Nixon, calling for “law and order” and promising to reduce crime by getting tough on criminals. The appeal to American voters to support “law and order” politics in 1968 meant especially that voters were favorably inclined to crack down on anti-poverty, civil rights, and antiwar mobilizations, the convergence of which was noted by Dr. Martin Luther King a year before his 1968 assassination. Scholars usually interpret “law and order” politics, in practice, by its results: the decimation of dissent in this country and the birth of the greatest carceral state the world has ever known, by far.

Nixon didn’t start the fires of coded racial warfare, but his successful adoption of post-Jim Crow coded racial politics (and a related ecology of imperialist and anticommunist authoritarianisms) nationalized and normalized it. Who doesn’t want “law and order,” after all? It’s not Jim Crow, and it doesn’t explicitly target labor and people of color. Compound this with the fact that many Black communities and their significantly religious political leadership mostly supported the idea of reducing crime and drugs. New York Representative Charles Rangel earned his political capital that way, and would partner with other white Democratic politicians like Joe Biden to pull the Democratic Party into a full-fledged bipartisan global War on Drugs in the 1980s.

Nixon’s “law and order” political agenda was, in practice, a mixed bag rather than a consistently applied doctrine. His administration funded addiction rehabilitation strategies that helped most of the mostly heroin-addicted Vietnam veterans go clean upon their return home, for example. And the fledgling DEA, born on his watch from the ashes of Harry Anslinger’s 1930s-style outfit, the Bureau of Narcotic and Dangerous Drugs, had nowhere near the institutional power and generalized legitimacy it would achieve under Reagan. As a Keynesian anticommunist Republican, Nixon also drew down the Cold War while paving the way for the neoliberal (read: anti-Keynesian) economic policy dominance we still live under. The “law and order” politician was also the most publicly criminal President we’ve ever had. The ironies abound, but the reality constructed out of these contradictions changed American politics like the 1960s changed American culture.

It’s taken a very, very long time for the politics of mass incarceration and militant drug warfare to begin to dislodge from the national political consensus consolidated during the Reagan, Bush I, and Clinton administrations. Quite frankly, it would seem we simply stopped being able to afford such costly and transparently counterproductive approaches. We are publicly broke while privately rich, as a country. So how would a throwback “law and order” politician (a) reconstitute the legitimacy of “law and order” and (b) pay for it? The first has to happen through the Attorney General, and faces potential backlash. And the second has to happen through Congressional approval of budgets. What Jeff Sessions thinks about people who consume cannabis is probably irrelevant.

It’s unclear whether or how either will happen, but the prospect has post-prohibition cannabis stakeholders much more nervous than they were under the Cole memo, Obama’s cannabis policy change vehicle, and certainly more nervous than what was anticipated under a Clinton II administration.

Much consternation has developed over Sessions’ personal cannabis politics, but let’s remember that the other options were probably Rudy Giuliani, the “law and order” former mayor of New York; and Chris Christie, who is also ardently anti-cannabis. Sessions will make his mark with a revision or replacement of the Cole memo (which formally made the rules for the Obama administration’ “laboratories of democracy” State approach under which cannabis policy has been nationally liberalized), but probably not explicitly as an anti-cannabis Memo. What Sessions and Trump share with establishment Republican discourse are the politics of State autonomy to deviate from Federal policy. Those politics lost the Civil War but won Jim Crow. And yes, they were largely code for racial politics that had to be overthrown with the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

But in 2016, State rights can mean a lot of other things besides or in addition to the power of States to roll back civil liberties established at the Federal level: Roe v Wade and gay marriage come to mind. The de-institutionalization of the drug war’s desirability, legitimacy, and economic feasibility has happened through Republicans like cannabis banking reform leader Dana Rohrbacher as well as Democrats. This shouldn’t be surprising, given that the drug war was and remains bipartisan political capital. Also, it was Republican intellectuals like Milton Friedman and William F. Buckley Jr. who publicly fought against the drug war when no one else would touch it for fear of losing political legitimacy. Those two are also libertarian political figures, and libertarian politics have largely been subsumed into the Republican party.

I doubt Donald Trump has a consistent political ideology: he’s a populist demagogue who can and does say whatever comes to mind first, and then figures out his actual policy approach later. When it comes to cannabis policy, I’m guessing that he’ll stick to the Republican establishment’s States rights discourse, and that will be the basis of the post-Cole memo to come through Sessions’ office.

Which isn’t all that different from the actual Cole memo. What are “laboratories of democracy” but the expression of State rights politics, applied liberally to the promotion of democracy as a socially beneficial national policy? The fact that States can choose democratic authoritarianism as well as democratic liberalism is irrelevant to the broader political meaning and potential outcomes.

Which is where I see the Sessions Memo potentially diverging from the Cole Memo. States, perhaps Sessions’ home state of Alabama, will be as free to conduct their own crackdowns on Federally banned cannabis markets as they are to tax and regulate them. Trump’s DOJ will be there to help them, just like Obama’s DOJ was when they asked for it. That’s the nature of the DOJ, as an institution: they work with State stakeholders to enforce Federal criminal law, but they generally can’t force it. They work through their State-institutional officers, the U.S. Attorneys, to do so.

So if you want to figure out what’s going to happen in your state, look for your U.S. Attorneys on the one hand and your State willingness to fund crackdowns on the other. The Sessions Memo, all other things held constant, will reinforce the quilt-like nature of the Federal crime policy blanket, where the Cole memo enforced the blanket nature of the Federal crime policy quilt.

The question of how it will be paid for, should it happen, is of great relevance. Unlike election words, which are really marketing gimmicks, the policies that result from political agendas follow funding. And our public sector coffers have shriveled up in the age of neoliberalism, which is really the age of monetary policy (Federal Reserve rate control) dominance over fiscal policy (government spending).

If there will be money for crackdowns, it is unlikely to flow exclusively through Federal agencies. Instead, look for “public-private” partnerships common to neoliberal governance. Look no further than how Trump plans to pay for the populist mega-infrastructure project to understand. Private corporations will bid on whatever “law and order” politics puts up for sale, and they will be provided with tax breaks and low-interest loans to carry out those agendas. Sales of military equipment to police departments will continue to flourish. This has already happened in California, where Blackwater-style contractors have been contracted to surveil and eradicate cannabis crops regardless of local jurisdictional notice or interest. I suggest that it will continue to happen in California, although the focus will shift/has shifted to the much more politically legitimate purpose of environmental protection.

Of course, all of this assumes that something unexpected happens to change the national cannabis policy calculus, such as Congressional action around the Controlled Substances Act upon which prohibition policy stands. Or something much more unexpected, a wildcard akin to Trump’s presidential victory.

In a recent interview with Rolling Stone Magazine, President Obama offered an intriguing peek into the logic of his mostly disappointing (to post-prohibition cannabis advocates) approach to cannabis policy change. As President, Obama enabled the Cole Memo but that’s about it, formally. His public politics have been ideologically consistent, however. He prefers post-prohibition approaches, but has insisted that institutional change at the federal level come from Congress rather than Executive Order. Whether one agrees with that approach or not, his compelling justification is that change that comes from Congress is likely to be on much more stable ground than change that comes through the Executive branch. It’s hard not to disagree, given Trump’s promise to cancel Obama’s executive orders and policies like the Affordable Care Act.

How does Congress change its mind? Congress changes its mind when, by sheer financial seduction or broad-based citizen action, individual legislators decide that the political calculus is in their favor and will help them get elected or re-elected. Obama has been telling post-prohibition cannabis organizers to figure it out.

The wildcard, however, is that perhaps Obama himself, as the most powerful of private citizens, will take a leadership role in fulfilling his own insistence that change happen through Congress. “I will have the opportunity as a private citizen to describe where I think we need to go,” he tells Rolling Stone.

This may be grasping at straws. But it’s pretty clear that Obama is the first person that who has been, at some point in his life, a stoner, to be elected President of the United States. This by the way is an argument that comes from my friend Vivian McPeak, organizer of Seattle Hempfest. The man was part of a clique called the Choom Gang while in high school. If he did decide to make post-prohibition a part of his post-presidential agenda, as a private citizen, it seems not completely farfetched that he would join up with the ACLU in their turn away from funding state initiatives to a national anti-mass incarceration policy approach.