by Dominic Corva, Social Science Research Director

***************

The opinions expressed in this editorial analysis belong to Dr. Corva, and do not necessarily reflect organizational consensus.

**************

As the July 1, 2016 deadline for Medical Cannabis markets in Washington State draws near, I would like to offer a few observations about how and why this phenomenon is nearly impossible to address, politically. There can be no focused essay, as a result, so I’ll offer a few openings on the closure of an 18 year trajectory in which patients in Washington State gained more access, until now.

First, a disclaimer. Our organization’s mission is to facilitate a peaceful human-cannabis relationship, which we cannot do by denigrating, stigmatizing, or dismissing any individual that grows, distributes, consumes, authorizes, tests, legislates, or regulates the plant. Nonetheless we have to deal with the fact that many if not most of the above people do this, to others, and that the coming re-creation of the Recreational Cannabis system into Boss of Medical Cannabis Access is the direct result of this happening. It was not necessary, but it’s what happened. My position is that this is the opposite of peaceful policy, and congruent with the extension of Prohibition culture into Regulation policy. And that we need to continue to work peacefully to get those “two steps back.” It all starts with accurate, reliable, and unpoliticized information.

- The WSLCB cannot fulfill their obligation under 5052 to ensure that patient access in Washington state is not disrupted on July 1. It has already been disrupted. I have personally had to scramble to make sure an older friend could replace the product she could no longer get, and have directed many, many inquiries towards the few Access Points that remain open.

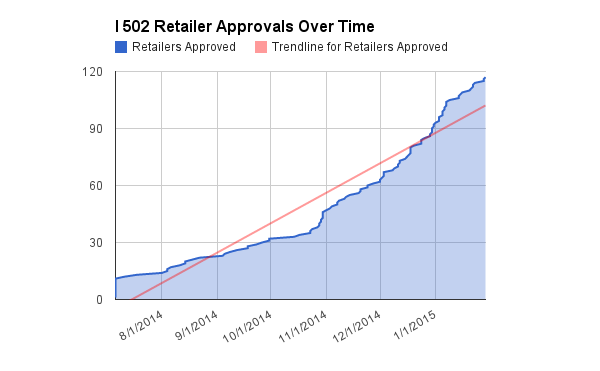

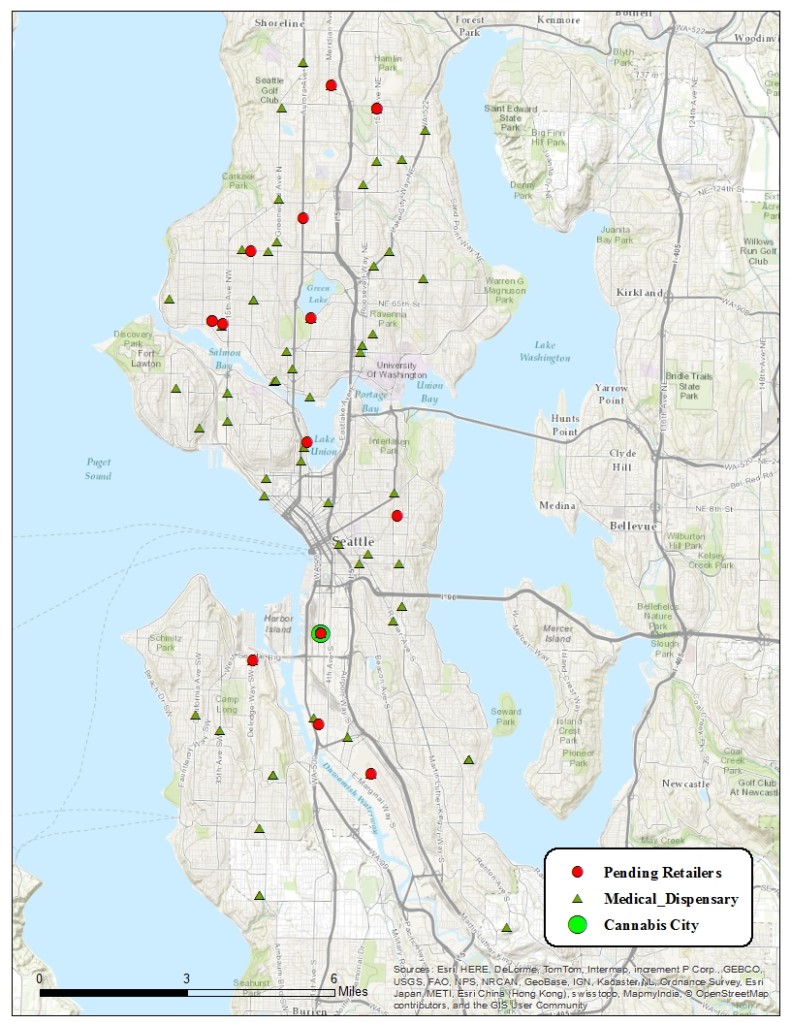

- There is also the matter of physical geography, product diversity, product availability, and affordability. The I 502 system won’t even get close to the kind of geographic access, access to diverse and specialized products, access to the amount and diversity of CBD rich products available in the access point system, and of course nowhere near the amount of access points previously available including delivery. And while cheap flower prices have arrived in much of the I 502 system, concentrate and edible prices remain far above those of their flower counterparts — and these are often widely preferred ways to consume for patients, for many reasons.

- Responsibility for reduced patient access in Washington State should be apportioned widely — the legislature, the LCB, the big money lobbyist, the monopoly-hungry trade association, the previous governor, the Majority Whip, the I 502 architect, the death-threatening activists, the patient advocates, the disorganized and fractured industry groups, the prohibition culture addicted to punishment, the law enforcement lobby, the UFCW, and more. We do not call for punishment, but responsible assessment of reality and its alignment with policy. And nothing responsible can be done unless people take responsibility for what has been done.

- Responsibility is something to which every one of these stakeholders seems to be allergic. Nothing that ever goes wrong is their fault, and everything that goes right has a raft of people ready to take credit. “Legalization” is an inflection point, historically and geographically; which means it’s both a continuation of what came before and the beginning of a new process that remains connected to all of the other processes that made it possible. No single organization or individual should be proclaiming victory, and there is way too much more work to be done. Legalization is not an endpoint.

- People often ask me about the black market. Even Clark County called me to ask about the black market. I told Clark County that their black market was now called “Oregon.”

- “Cartels” haven’t had much of a market share in the Pacific Northwest, maybe ever. This State is the birthplace of indoor cannabis. The original owner of Fremont’s Indoor Sun Shoppe wrote the first indoor grow guide ever published. It was 1972, and his shop was located on University Avenue across from the campus. Also I don’t think we call Southeast Asian-Canadian organized crime from BC “cartels,” but their dominance went into terminal decline at the turn of the century.

- The Washington black market, “domestically,” can be found on every college campus in the state and all of its music festivals. Access points hit lots of “middlemen” hard, but perhaps the dorm room dealer most of all. Things are looking up for dorm room dealers, street dealers, and small personal network dealers. That might be a good thing, since it’s a windfall for economically marginalized populations.

- NSDUH statistics show that people under 21 (read: college students especially) constitute the biggest cannabis-consuming demographic there is. As long as cannabis is legal only for “over 21” adults — as opposed to people who can vote, get a credit card, and join the army as “over 18” adults — the State will hit a wall in its efforts to eliminate the black market, no matter how low prices go. The U.S.-American higher education system will welcome cannabis culture and markets until the last dorm room gets turned into a prison cell.

- The black market that the State doesn’t address by shutting down “gray market” access points is called the export market. It’s been going on for decades, and closing medical does nothing at all to those exports.

- There’s a new black market, and it’s called diversion from the I 502 market. No one wants to talk about it, but somehow I still can’t avoid running into it. An interesting irony: I can hear folks talk all day long about state, interstate, and global black market developments but the minute anyone accidentally or on purpose mentions seeing I 502 diversion they shut up completely. It’s more dangerous to talk about than normal felonious activity. Disclaimer: the previous sentences in “point number 10” are hypothetical, I’ve never heard of nor seen diversion from the I 502 market. I don’t know what I was talking about.

- SB 5052’s new “four person cooperative garden” provision is a mystery. It has to be located in people’s domiciles, which would indicate that whatever happens there is protected by privacy laws, so … are there supposed to be cameras? where are registered patients supposed to get their plants? Is it a 15 day window 365 days a year? Has anyone signed up for this, a little over a month before “collective gardens” become illegal? In fact, how many patients have signed up for the registry so they can save 10% sales tax on their “medically endorsed” purchases? I’ll let you know as soon as I hear back from my public information request.

- Will there be a Kleiman-recommended huge crackdown, by Federal and/or other law enforcement agencies, immediately after July 1? Mark Kleiman has in many places recommended a big crackdown to “break the back” of the black market as soon as a regulated system is in place.

- I suspect there won’t be the budget nor the political will to make examples of home growers, but I do expect unregulated warehouse grows to be targeted and Federal investigations that have been pending for a few years to conclude.

- A legislative home grow option, especially if pitched as a “home brew” provision, would deal with many of not most of the problems caused by the hostile takeover of medical cannabis markets by the State. It will happen eventually — every other state has one, and California’s direction will steer the national policy ship once either AUMA passes or, if it doesn’t, once its legislature takes on the task of legalizing and regulating. But here in Washington, I keep hearing “some time in the next couple of years” from lobbyists and legislators.

- The I 502 system is never going to be a failure — it’s a conspiracy to sell weed without fear of enforcement, how could it be, but it is going to be full of individual failures, especially from small businesses. I’m aggressively uninterested in “$X billion sold” headlines and extremely concerned that X out of that X billion will go to a very few people rather than support small farmers, who will cash out and sell to investment groups as the rules and rule implementations evolve away from what used to be an advertised State concern — the protection and promotion of small businesses.

Thanks for reading! Again, the opinions expressed in this editorial analysis belong to Dr. Corva, and do not necessarily reflect organizational consensus.