by Dominic Corva, Executive Director

As Oregon moves towards the Washington model for legalizing cannabis, it’s important to document how, why, and who. This letter came to us on a listserv email, as a response to Oregon cannabis organizers questioning why State Legal Cannabis now seems to preclude preservation of the existing Oregon Medical Marijuana Program (OMMP). This post reproduces Senator Kruse’s letter as it came to us in an email: it may have been abbreviated or altered in transit. If so we are happy to make corrections.

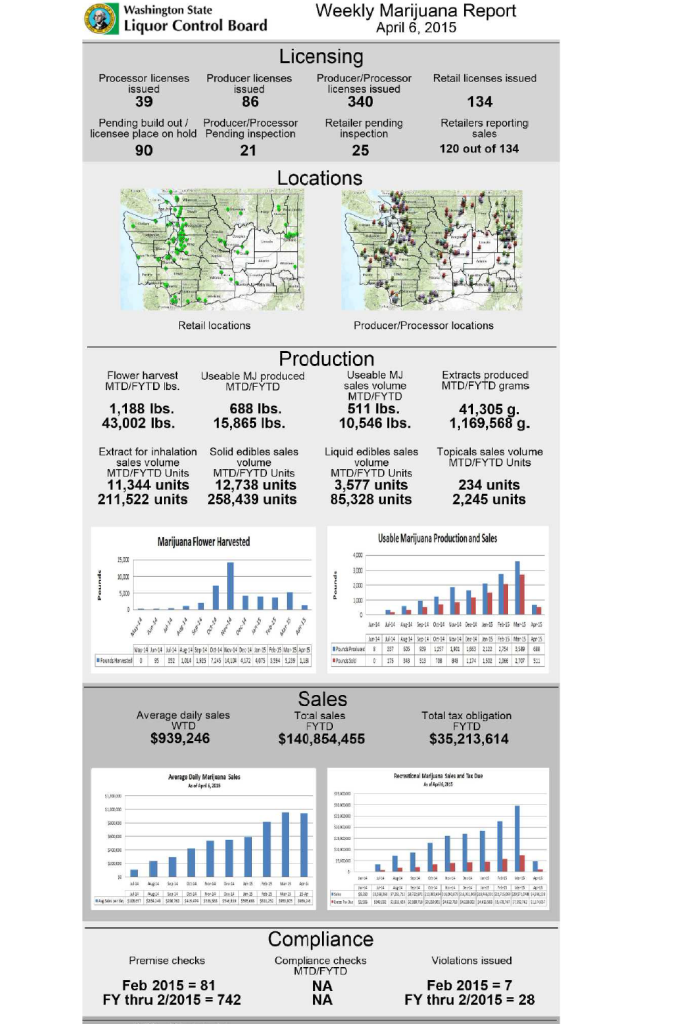

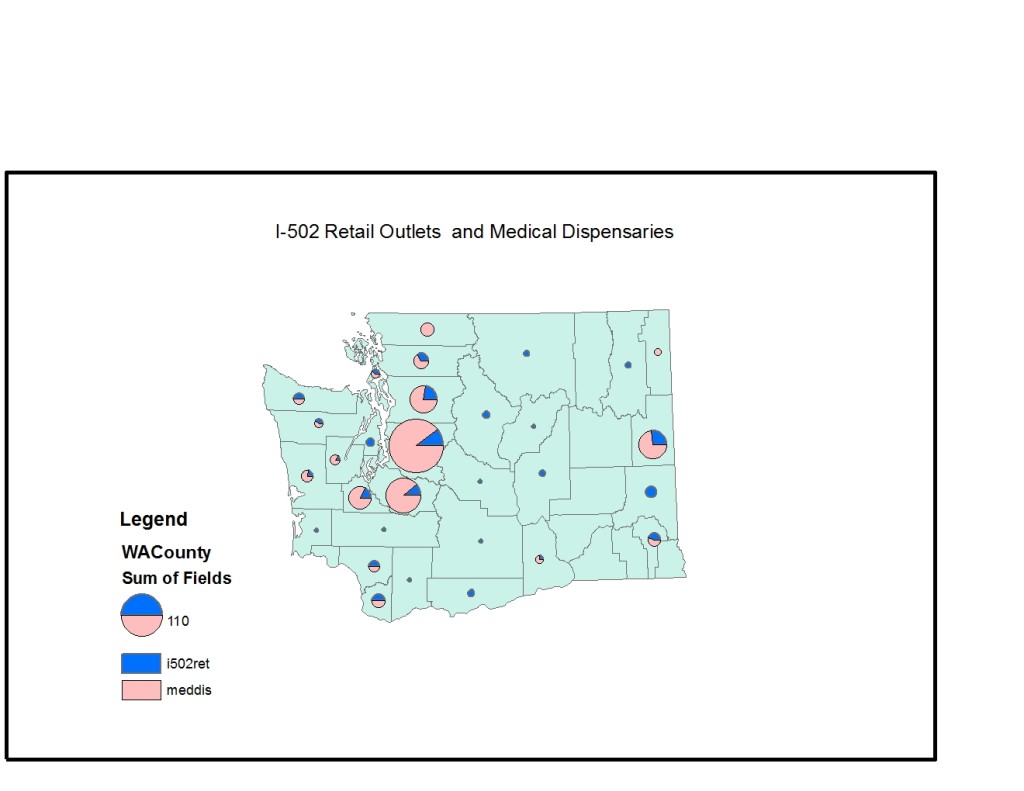

There are many political and economic rationales at work to turn cannabis legalization into a reason to radically restructure medical cannabis regulation, but this letter highlights, in no particular order (1) perceived political pressure from the Federal Government; (2) perceived lack of regulation despite Oregon’s existing medical regulatory framework (as opposed to Washington, which didn’t have one on account of then-Governor Gregoire’s 2011 section veto); (3) deference to minority voter will; (4) backlash against “vulgar and threatening” approaches by some cannabis activist communications; (5) and belief that it is possible to end black market sales in Oregon through legislation this session.

Only one of these rationales is totally detached from reality — the last one. It’s unclear to me how legislators don’t grasp the regulatory reality of 40 years of prohibition — an effort to legislate and enforce the black market out of existence. It doesn’t work, and that’s why voters are passing legalization initiatives. Or rather, it does work: it works to create cannabis informal markets that respond to price differentials across space. In Oregon, this has meant the development of a major export market. This did not happen overnight, and it was not the result of medical marijuana regulation. Ending medical cannabis regulation does not and can not mean ending black market sales in Oregon.

Other than that, all of the other rationales have some purchase in reality even if they support the counterproductive aim of excluding people from society rather than bringing them in from the shadows. They establish lines in the sand over which the future of Oregon, and United Statesian, cannabis legalization are being contested. From our perspective, here are a few counterpunches:

(1) Federal government cannabis policy has always been fear-based, not evidence-based. Legalization cannot achieve its social purpose — ending the drug war — through fearful deference to Federal legal categories and threats.

(2) OMMP is as much about legal protection from an insane drug war as it is about protecting the right to health. Colorado’s regulations are no more strict than OMMP, and the Federal government has shown no signs of interference.

(3) Protecting the rights of minorities is a great democratic goal — but in this case, the voting minority is morally wrong: continuing the failed drug war on a county- and city-level patchwork geography is bad for society and will doom efforts to create a statewide cannabis peace experiment.

(4) How we communicate is just as, if not more, important than what we communicate. Rude and threatening communication from 2014’s session ensured that key lawmakers in the 2015 session allowed only I 502 business interests to influence their thoughts and decisions about medical cannabis in SB 5052. We at the Center believe that nonviolent engagement is the best strategy for winning hearts and minds in the drug peace movement.

That said, I present to you Oregon Senator Jeff Kruse, R-Roseburg. The message has been copied and pasted from email without alteration.

***

*”Working Hard For You*

*MAY 22, 2015*

*POT…..AGAIN*

I have received a lot of phone calls and emails on the subject of

marijuana, which advocates say we should call cannabis, but for the sake of

brevity in this letter I will call it pot. While a good number of these

have been thoughtful and courteous, a large number and been vulgar and even

threatening. To those in the latter category, if you are trying to make a

valid point with a legislator, you are going about it the wrong way. I

can’t speak for my colleagues, but personally I don’t respond to such

tactics and have little respect for those who use them.

Before I go any further it might be a good idea to once again tell you why

I am qualified to be working in this subject area. First, I am a

recovering addict. I have been drug and alcohol free for 29 years; but,

among the other things I did, I was a daily pot smoker for eighteen years.

Additionally I have been involved legislatively with the medical marijuana

program since the passage of the ballot measure in 1998. I entered this

Session with a lot of thoughts, but two primary objectives. The first was

to protect the integrity of the medical program and the second was to

attempt to end the black market sales in Oregon. Senate Bill 964 (which

deals with the medical program) goes a long way to achieving those

objectives.

Many have asked why we are dealing with the medical program when Ballot

Measure 91 was about recreational use. The short answer is because of the

direction we have received from federal government on the subject. We need

to remember that pot is a schedule 1 narcotic at the federal level, and

they expect a much higher level of accountability than we currently have in

the system, which is actually no accountability at all. For example, if we

assume two pounds of pot for each of the 71,000 patients that would give us

a total of 142,000 pounds accounted for in the system. However, the

conservative estimates from OSU tell us there is well over a million pounds

being produced (and other estimates take us to a much larger number).

There is clearly no way we can claim we know where the pot being produced

is going, but one would have to assume it is going into the black market.

According to the Cole Memorandum from the US Department of Justice this is

a red flag which could jeopardize the recreational program. SB 964

includes a tracking system which, with the support of the Governor’s

office, will satisfy the feds on the issue of accountability.

The issue that split the Joint Committee was the local option relative to

the location of dispensaries. All of the Senate members of the committee

wanted a local option provision, but three of the five House members

didn’t. Over that issue the committee split and a Senate-only committee

was created, which passed out SB 964. For those keeping track of such

things, if the House had agreed it would have been SB 844. Our version

allows a local jurisdiction (city or county) to decide if they want to

allow dispensaries, including the time, place and manner of the

operations. It has two other provisions, one which would allow the people

to put a measure on the local ballot with only 4% of registered voters

being required and the second gave local governments 180 days to decide to

give adequate time for people to put something on the ballot. It should

also be noted all existing dispensaries and those that have gone through

the permit process would still be in place. We are hoping to get similar

provisions on tracking and local options in the recreational bill, which is

currently HB 3400 (which we just started working on).

An interesting side note on “the will of the people.” Clearly the voters

passed medical marijuana in 1998 and we have been working to improve the

system since that time. It is also true the people passed Measure 91 at

the last election, which compels us to implement the recreational program.

What I have always found to be interesting is what is defined as an

“overwhelming majority.” In the case of Measure 91 the yes votes were 56%,

which for some reason qualifies under the overwhelming category. What

tends to be forgotten is the fact 44 out of 100 people voted no, which I

think is actually significant. What I mean by that is the fact that those

who voted no should not be totally ignored. As a Senator I don’t represent

just those who voted for me, I represent all the people of my district. I

personally don’t think 56% is overwhelming, especially when in some parts

of the state the vote went the other way. This is the primary reason I am

supporting the local option, because I would prefer the state not dictate

to communities much in the same manner I don’t like the federal government

dictating to the states. My favorite example is the education system. The

more the federal and state governments have been dictating to school

districts, the worse the outcomes have become.

The legalization of marijuana is a major change in this state. We are

committed to doing what we can to make sure we do it right. I just think

it is important to not step on the rights of communities and the people in

those communities in the process.

Sincerely,

Senator Jeff Kruse”