by Dominic Corva, Social Science Research Director

Legal Cannabis Phase I, for our interview subjects, overlapped with another State legal regime, Initiative 75, which was codified as RCW 69.51.A in 1998. Washington State medical cannabis laws were first passed by citizen initiative in 1998 and amended legislatively multiple times until 2011. The 2011 amendment, SB 5073, was a legislative bill requiring the State to regulate and tax commercial medical cannabis. It was the culmination of over a decade of then-Senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles collaboration with Washington State medical cannabis patients and stakeholders. Those efforts continued for four years, until SB 5052 swallowed them up by folding medical cannabis regulation into the I 502 framework in 2015. First, let’s clarify this timeline, and then let’s discuss how this is relevant to our study of Legal Cannabis Phase I.

The timeline goes something like this.

- Medical Phase I: 1998- April, 2011. Key legal framework: affirmative defense for possession; evolving criteria for authorizations; and evolving plant counts.

- Medical Phase II: April 29, 2011 — July 1, 2016. Key legal framework change: commercialization tolerated in policy, especially in Seattle and King County, via a noncommercial clause, “collective gardens.”

- Legal Phase I: I 502 (December 2012/13 — April 28, 2015/July 1, 2016). Key legal framework: an explicitly non-medical system regulated by the WSLCB.

- Legal Phase II: July 1, 2016- . Key legal framework: a single integrated medical and non-medical system regulated by the WSLCB, plus other reforms to the 502 law.

5. Overlap: April 28, 2015-July 1, 2016. Medical Phase II and Legal Phase I co-exist.

This timeline could easily be broken up further. For instance, the 2008 liberalization of authorization authority had a significant impact on the availability of authorized consumers for access points. And the 2011 legislative vehicle was the first of Senator Kohl-Welles’ reform efforts that sought to regulate patient access, rather than improve patient access. Between 2008 and 2011, something or some things happened to centralize legal reform efforts away from “more cannabis and more patients” to “discipline unruly State cannabis markets.” This is the subject of another book or chapter, however.

Instead, we want to understand the dynamics of Medical policy and markets as continuous and parallel to the dynamics of Legal policy and markets. And to do that, we have to unpack the evolution of both processes in relation to and separate from each other. We want to use Medical Phase I to break up and analyze Legal Phase I as the upstart — or start-up — framework with messy and unanticipated dynamics, not a homogenous legal time in which one thing logically followed another until it was time for Legal Phase II in Washington State.

In fact, the reason they evolved separately had less to do with the passage of I 502 than the way the WSLCB chose to implement it. And the way they chose to implement it was to create a completely different system rather than to use State Medical markets as a foundation. This is probably the defining characteristic of the “Washington model,” since no other state has chosen to do it that way.

The WSLCB took about 10 months to go from figuring out what cannabis was at the most basic level to implementing a “starting from scratch” model. For the first six months or so, that process was dominated by public and private meetings across the state so the Board could learn from existing cannabis market stakeholders a few things about the commodity they were charged with regulating. Starting in about April 2013, that process overlapped with a more academic exercise, in which BOTEC was contracted to estimate the size of the cannabis market, its potential environmental impacts, and so forth.

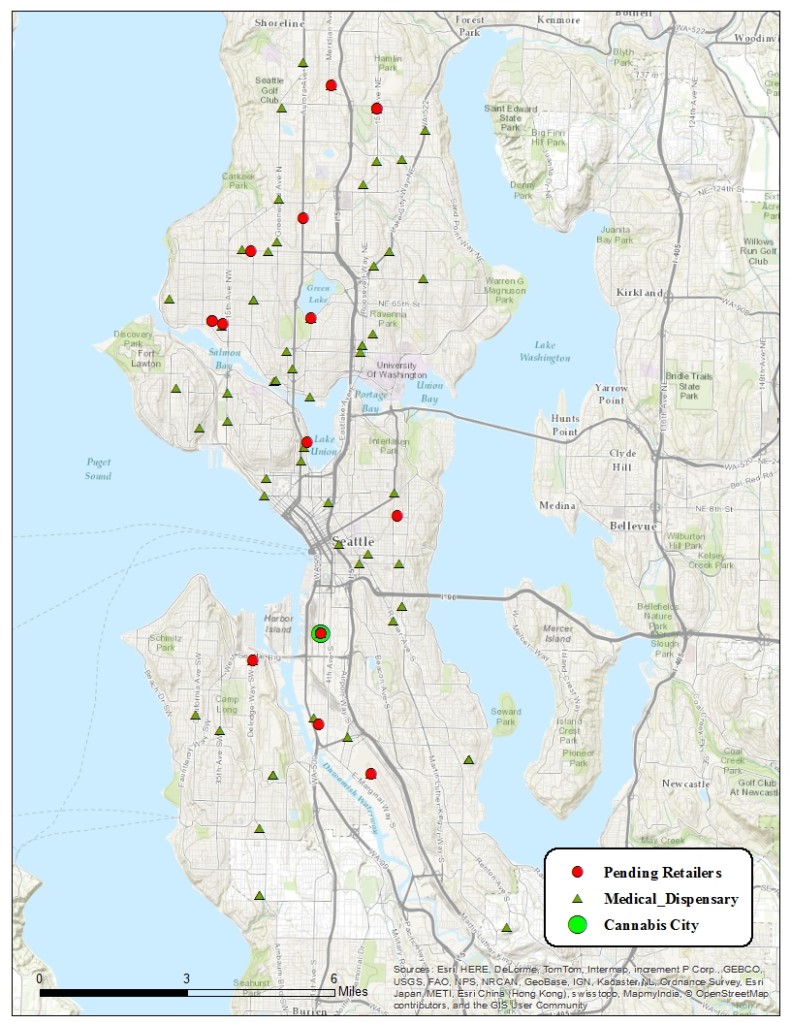

By the fall of 2013, the WSLCB had decided on a course of action that may or may not have been understood by the bureaucracy itself as a model for starting from scratch. There would be a one month window for applications, some time to process producer and processor applications, and then a lottery for retail applications, then some time to process those, and then by June 2014 Legal Phase I would open for business. This is a well-known timeline, but we emphasize two things about it that are poorly understood.

First, the applicant pool was much larger and different from what the WSLCB expected. Instead of a few hundred experienced applicants, they received a few thousand applications, many of whom were “gaming the system” by forging real estate claims and creating rings of applicants from friends, family, or straight up business associates to maximize their odds in the retail lottery or gain control of more canopy than they could otherwise.

And second, applicants to the 502 system were applying to a system that was legally forbidden from making any medical or therapeutic claims about cannabis. Although some of our interview subjects anticipated that this would change, it was a great disincentive to existing Medical Cannabis stakeholders against joining the I 502 system. This applies especially to retail access points, whose products and customer base revolved centrally around making those claims. But it also applies to producers and processors, since medical markets themselves continued to evolve away from simply growing high THC sinsemilla flower, towards CBD-rich cultivars, extracts, and edibles of much greater potency and diversity than would appeal to “recreational” consumers in the new system.

The takeaway for this post is that while the WSLCB may or may not have intended to “start from scratch” with I 502 stakeholders that were overwhelmingly new to cannabis, that’s how it worked out. This is most clear for the retail side of things, in which the lottery system could have by chance favored existing Medical Cannabis access points, but the odds were pretty slim given the amount of applicants and the way they gamed the system.

This is how it shook out for our interviewees. One of them “won” a lottery position outright, but was derailed repeatedly over real estate and business partnership issues. One of them acquired a Shoreline lottery position very early, and once a few of the winning lottery positions failed to take advantage, had their Seattle number come up. They have a Sodo location now. Two others drew extremely low lottery numbers whose numbers never came up. And one did not apply at all, figuring that the two systems would remain separate given that the 502 system was not allowed to be medical in any way. We will address who these are, and how this process shook out, in the book.