by Dominic Corva, Social Science Research Director

Yesterday’s White House press conference comments about the Trump Administration’s approach to legal cannabis sent the cannabis press into a frenzy of fear, anger, and a little hysteria. A superficial reading of Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s comments signaled the first clearly negative tone about Department of Justice (DOJ) enforcement against State-legal cannabis/marijuana experiments, but let’s take a closer look at what he actually said and add some context to defuse some of the hysteria about a “crackdown” while pointing towards what it actually might mean.

The first thing to notice is that Spicer said nothing about enforcement against State legal cannabis based on Federal conflict. Rather, Spicer echoed Jeff Sessions’ earlier comments about whether the 2014 Cole memo itself was being enforced, and consistently referenced existing policy structures at the federal level. Further, the question he was responding to was from an Arkansas reporter concerned about Arkansas’ recent medical cannabis legislation. It’s clear this response was meant to reassure Arkansas, which is why Spicer really didn’t say much new about recreational cannabis.

He begins by making a distinction between medical and recreational cannabis, highlighting a general Administrative perspective that not only favors medical cannabis in principle, but respects the existing Congressional appropriations rider that forbids DOJ enforcement against medical cannabis businesses that are compliant with State law. The link I provide here not only describes the legislative directive, but reports on the Court victory that gives it more legs than just a directive. This means the DOJ has already lost an effort in the judicial branch to overturn it. The DOJ doesn’t like losing money and court battles, so we can read this as doubly-armored protection for existing Federal medical cannabis policy.

Arkansas, Spicer is saying, is safe to proceed with constructing a medical cannabis regime. A second reporter jumps on the distinction he made, which was meant to highlight how Arkansas medical cannabis isn’t in danger, between recreational and medical cannabis. And he punts it to the DOJ.

At 2:35: “that’s a question for the Department of Justice, I do believe that you’ll see greater enforcement of it.”

The question is, what does he mean by “it”? In all likelihood, he means what Jeff Sessions clearly meant in his confirmation hearings when he discussed the Cole memo.

This is what he said: “”I think some of them are truly valuable in evaluating cases,” Sessions said Tuesday about the [Cole] guidelines. ‘But fundamentally, the criticism I think that was legitimate is that they may not have been followed. And using good judgment about how to handle these cases will be a responsibility of mine.””

The Cole memo guides DOJ enforcement policy, not against legal cannabis, but against legal cannabis diversion to other states, to minors, to double-dipping (using legal cannabis businesses as a cover for State-illegal market operations), drugged driving, and so forth. This means that the Feds reserve the right to enforce against legal cannabis businesses where State enforcement is deemed insufficient.

This is extremely different from “cracking down on legal cannabis.” My reading concludes that the Feds reserve the right here to supplement State enforcement of their own legal cannabis businesses that are not in fact compliant with State law.

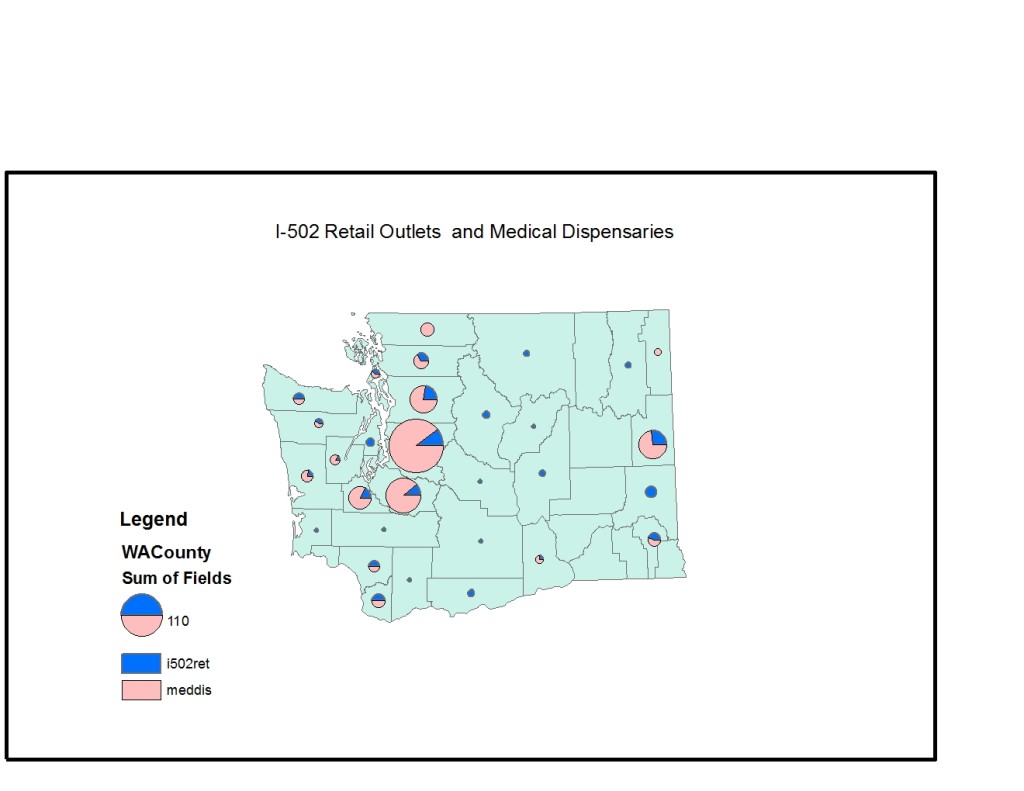

The caveat here is that this is probably a much, much larger portion of the legal cannabis market than States would admit. Oregon cannabis organizer John Sajo has distinguished between “tightly regulated” and “tightly controlled” cannabis markets. The former is basically political theater, in which seed-to-sale tracking systems are effective because they exist, rather than because they work very well. Why they wouldn’t work very well isn’t hard to see from inside a legal cannabis business, but no one — especially not State regulatory agencies — has any stake in advertising the fact that there are simply not enough human resources to comb through thousands of hours of surveillance data before they can be destroyed in a 30-day window, for example.

“Tightly regulated” should be seen for the political theater that it is, reassuring key worriers (the Feds, State governors, legislators, the anti-cannabis culture that remains dominant even in legal cannabis states) that there’s nothing to see here because we are compliant with the Cole Memo. “Tightly controlled” is a prohibition fantasy, as it always has been especially with respect to a plant.

The take here is that Spicer, via Sessions, has indicated that the DOJ will do some enforcement of the Cole memo, against market participants not State systems, not that the DOJ will “crack down on” legal cannabis regimes wherever they might be. I would hazard to guess that Cole memo enforcement is probably more likely in Colorado, rather than Washington and certainly nowhere there isn’t even a legal system in place yet. It takes at least 2 years from initiative passage to market and oversight functionality, so Oregon is kind of the next closest in terms of viable enforcement logic, and they have recently passed the stage where Spicer’s comments would be particularly relevant (ie, when unregulated adult purchases were permitted at licensed medical stores).

Nothing in the press conference indicated that the Feds were coming after public officials or attempting to stop legal cannabis implementation in say California. This didn’t stop California and Washington from “signaling” right back, just in case. It should be noted that both of these States have been making political hay out of refusing to cooperate with Federal immigration enforcement under the Trump administration, too.

The Trump administration, if it is consistent with anything, is consistently nationalist. Which means most of its political enforcement theater will be directed at issues that can be attributed to things that come from somewhere else, such as the greatly exaggerated supply of cannabis from transnational criminal organizations aka “Mexican cartels.”

Then there’s the matter of resources for a “crackdown,” which would be politically difficult. Trump’s DOJ is extremely busy doing other things that will undoubtedly take a toll on their prosecution budget as well as test the limits of the public’s tolerance of Executive freestyling. It’s an open question whether his base would support much DOJ activity that would run counter to state’s rights issues that don’t directly implicate cross-border trade and migration.

Cannabis politics are pretty diverse and often right-wing — there’s nothing inherently progressive about schemes to tax and regulate something that is consumed like a commodity by so many. After four years of ethnographic immersion, it seems to me that Whole Plant, Whole Society politics remain limited to legacy farmers, cannabis culturalists, and medical patients — none of whom are served very well by cannabis legalization.

From this perspective, the hysteria over Spicer’s comments yesterday is particularly flavored by commodity cannabis interests, on the one hand, and anti-Trump State politics on the other. Those who’ve been involved with cannabis policy longer than say two years aren’t particularly fazed by what the Feds do or what the States say, primarily because we recognize how this is not so much something new as an organic evolution of Prohibition culture and democratic authoritarianism at large.