by Dominic Corva, Social Science Research Director

Today’s post examines the meaning of “community” as it intersects with both “culture” and “cannabis.” Let’s start with anthropologist Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities” (the title of his 1983 publication). Anderson’s big contribution to social theory reconstructs the meaning of community as a signifier of common identity, especially as it applies to the emergence of national identities. Really he was taking part in a social theory turn that was about how social identities are constructed and performed, rather than biological or natural. A good example of this is the concept of “race,” which before the 20th century was a term applied to ethnic and national identities rather than common skin tones: the Irish race this, the Italian race that, and so forth. It was all about the process of defining Selves and Others, and usually had a territorial as well as biological connotation. A community is a group of people who are imagined to be like each other, and nations are “imagined communities” in the sense that all their differences get subsumed under a few common identity markers, one of which is having a place of origin or belonging in common.

But having a place of origin or belonging in common, and having that marker of identity mobilized, can often mean that a great deal of internal difference is being erased, often violently. Okies from Muskogee can only be Okies from Muskogee if they don’t smoke marijuana or take LSD, according to Merle Haggard, but Dr. Sunil Aggarwal has often contested that assertion. If it’s true, then he doesn’t get to belong to the place he grew up. Hence nationalism — and all other imagined community identities — are political: who gets the final word depends on power in social relations, not who’s technically right. The power to define community is the power to include or exclude.

So what’s the cannabis community, exactly. I experience a lot of positive and a lot of negative meanings associated with that post-ethnic identity marker, which can be and sometimes is framed in terms of nationalism. Some mourn the loss of community as cannabis becomes commercialized and inserted into the formal capitalist economy. Some celebrate the opening of cannabis community membership into the ecology of legally sanctioned communities subsumed under national, State, and local identities. What’s the Washington cannabis community like, and so forth.

The challenge for this post isn’t to define what “the cannabis community” is or might be, though I have a few strong feelings about it. The challenge for this post is to identify community formation as an ongoing and vital part of social survival. Communities are always being lost, broken, made, healed: they are created by performing common ground, and they have to be constantly re-created and renewed to gain political and economic purchase on the ecology of community formations in society that aren’t punished for existing.

I must admit I’m pretty ambivalent about “cannabis community” as a singular concept, sweeping up difference under the rug of community. I find that when it’s singularly deployed it tends to be either deployed as a brand, on the one hand, for getting people to buy things; and as a stigmatized group that isn’t allowed to participate in “modern” legal cannabis markets, events, or even spaces outside one’s own home on another end. I find it more useful as a term of aspiration or auto-critique, usually associated with efforts to be together on something or an acknowledgement that the failure to renew community and mobilize it in a productive fashion has created missed opportunities for the cannabis peace movement from which we should learn.

That’s not terribly specific, I know, but this is not a space for dictating how folks who’ve found cannabis therapeutic in their lives should shape their identities. I’m specifically anti-identity in many ways: I’m less interested in what we have in common than how we can peacefully coexist despite our differences, because we are interdependent at the very least in the spaces we share. But the practice of calling a community together can help considerably in the search for peaceful coexistence.

The way we are organizing for peaceful coexistence involves the production of popular education events. Our Terpestival is a whole plant conference: the focus on Terpenes helps decenter approaches to centralize the meaning of cannabis, and therefore what cannabis communities can be. That problem of centralized meaning is not just a negative power function — “dangerous drug”, signifier of “Bad Actor,” and so forth — but a positive power function with negative effects. The focus on low cost THC production for prohibition markets has dramatically limited non-cannabis communities’ willingness to step away from stigma and let the plant be a plant.

That model, interestingly, is now being perpetuated in Washington’s legal system for public and private reasons. The State wants revenue, and it gets the most revenue when retailers copy the prohibition market’s tendencies toward highest THC and lowest prices. At the same time its onerous regulations make THC information on the label the most reliable information available to consumers (and budtenders) who aren’t allowed to smell the flowers or sample the product. Combine that with the McDonald’s fast-food high volume business model and it’s no wonder cannabis is becoming just another commodity here. And communities based on commodities have a name: industry. Not much room for cultural difference and community formation there, except as ways to brand, market and sell things.

Which is, I suppose, the proverbial American way. It’s the familiar same-old centralized national identity subsuming all of the differences that constitute our social ecologies under the generic flag of consumer identity. It works, for a lot of people in the cannabis industry — especially the new ones, intent on producing a tornado of creative destruction out of which they build their empires of exclusive wealth and individual glory. I’m just not into it.

But it’s not enough to be “just not into it.” If I want cannabis community — and I desire a cannabis community of decentralized differences that peacefully coexist — I have to create spaces where other people can understand what I desire and desire it with me. Also at the same time I have to navigate the social ecology of acceptable and tolerated communities who feel threatened by my cannabis-positive values. I have to understand what they are afraid of, and not get frustrated that their fears are irrelevant even if they aren’t based on evidence. And I have to find and work strategically with people who share my values and are able to act on them.

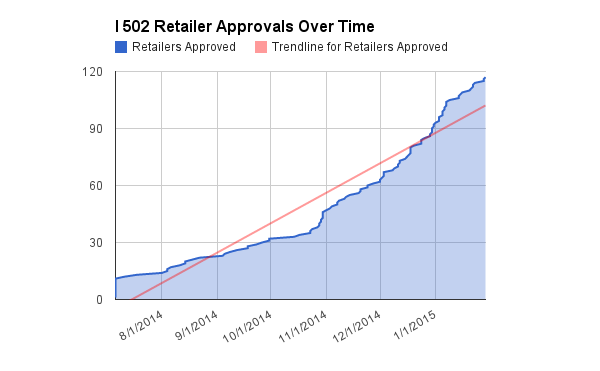

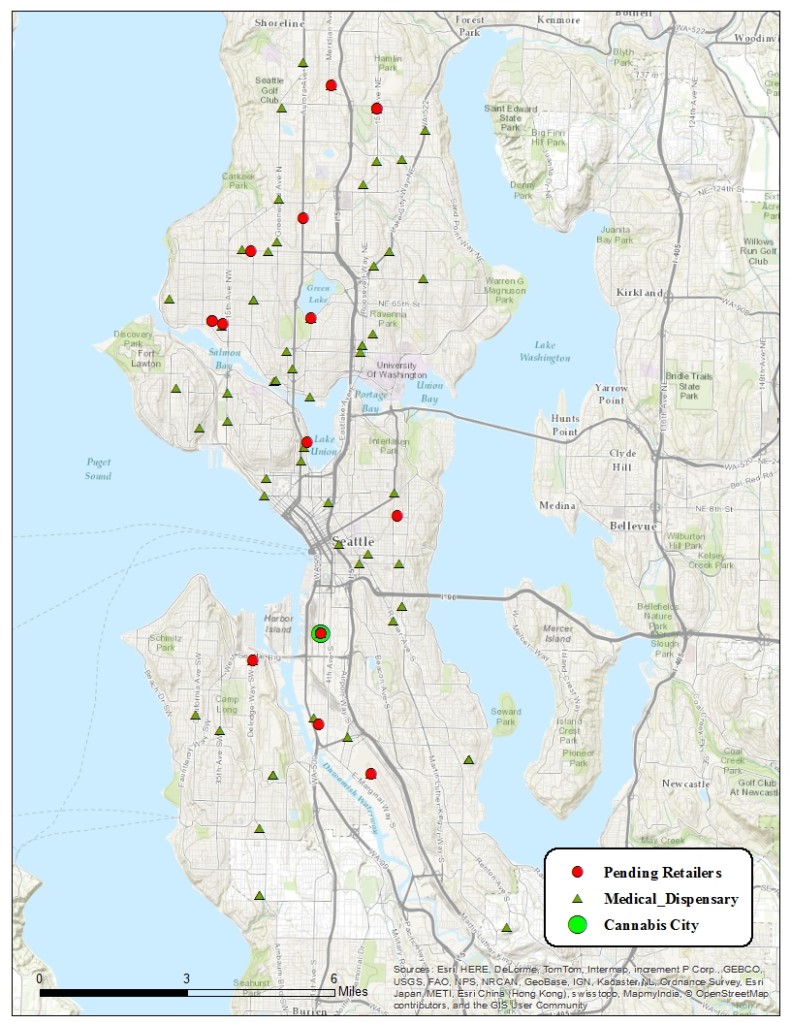

This last point is crucial. The re-criminalization of medical cannabis in Washington State has meant that for the last year at least, people who share my values — chiefly, that cannabis is a plant with many, many beneficial uses and the problems attributed to it are caused mostly by its prohibition and stigmatization — have been losing their jobs, losing their margins, and transitioning to a new system in which margins are vanishingly small and controlled by people who put profits over social peace. Washington’s model of legalization has certainly made cannabis communities everywhere more afraid of legalization, and that can’t be a good thing.

It’s not a good thing for a lot of reasons, but I’ll point out an especially Big One. Cannabis legalization is first and foremost about getting people out of jail and ending the drug war — both of which affect communities of color disproportionately. It’s not really about cannabis, it’s about the practice of prohibition — which was never about cannabis, but about social control. We need legalization to happen to end the drug war. It’s that simple. But we need models of legalization that care for the hundreds of thousands of people that see themselves part of a community that is under attack. There’s no reason why ending the drug war can’t also promote livelihood continuities and broader spaces of social peace. No reason at all.

But there are no cannabis peace stakeholders at the table, because cannabis communities have always been marginal to society. They aren’t at the table even to write initiatives anymore — that process is clearly being privatized. That marginality is cultural, not just “forced” upon cannabists: cannabis consumption, production and distribution under conditions of prohibition have been carried out largely by people who are culturally disobedient — the counterculture.

This is a fundamental tension that prevents cannabis communities from having a voice in how things are changing. What’s to come is going to depend on how people imagine their communities, and whether those people find a way to act together and actually perform those communities.